This is a (very slightly) provocative and informal perspective on what we understand as Viking economic networks and economic sites.

Rethinking ‘Economic Sites’

In the first instance, I suggest that we need to think of ‘economic sites’ – by which I mean any place where people are involved in commercial transactions using any form of currency or credit – as one where at least two individuals engage in such activity.

If we are serious about continuing our shared endeavour of ‘deconstructing monolithic perspectives’ and restoring full agency to ‘sophisticated and dynamic’ groups across the Viking world, we would be well advised to apply this to all economic sites, whether the site in question is an individual or family group on an island in the Scottish Hebrides like Bornish [Bornais], or in a permanent market settlement with urban characteristics in Scandinavia like Birka, Hedeby, or Kaupang.

We should, then, think rather less about type sites, or rather ‘types of sites,’ when we consider trade and economic exchange and, instead, focus on the two most important aspects; namely the individual acts of transaction and the networks that made these transactions possible.

I’m arguing here that we should spend more of our energies looking at the smallest (i.e., basic transactions) and largest (i.e., network) perspectives and move – at least slightly – away from permanent and temporary market sites as our initial point of departure. (Note that this argument comes from someone who has and will continue to argue extensively about the importance of the nodal market sites and overwintering army camps as market places and anchors of networks!).

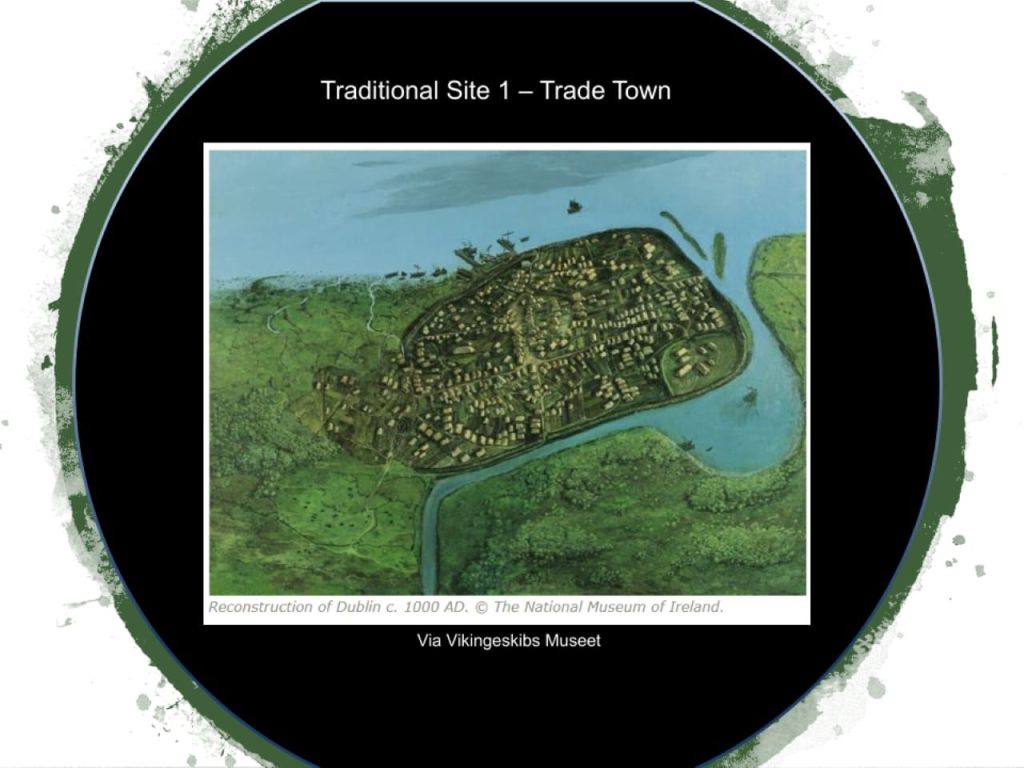

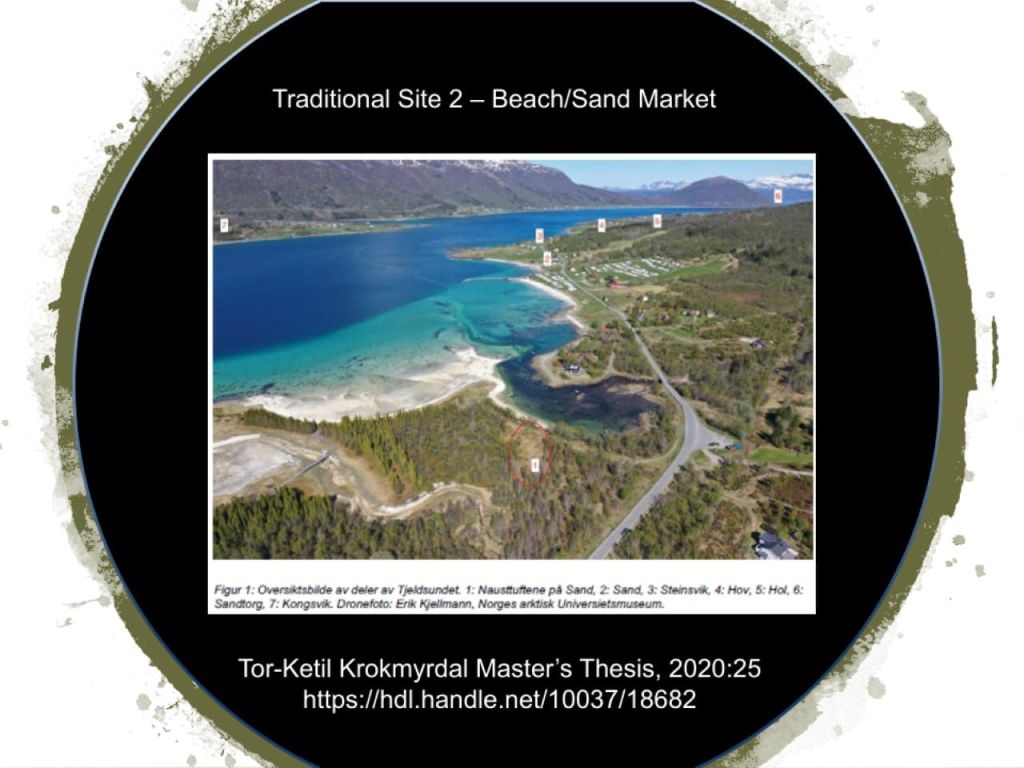

Of course, towns like Birka, Kaupang, Hedeby, Jórvík and Dublin are, quite literally, central places for economic development and our studies thereof. This is also true for the more ephemeral economic sites, including the Sandtorg i Tjelsund beach/coastal market in Troms discovered recently by Tor-Ketil Krokmyrdal, Great Army winter-camps like the River Trent ‘cluster’ between Repton and the recently-discovered Foremark and the ‘Near Felton’ Coquet Valley site; and longphuirt like Woodstown.

We can see these types of site here:

© National Museum of Ireland

© Compost Creative

However, if we persist in the Viking-Age equivalent of antiquarian Roman wall-chasing and base our view of ‘typical’ trade on these more prominent sites, we risk ignoring the everyday transactions in the homes and hamlets that, presumably, made up the unglamourous majority of economic activity.

The Rural Perspective

In this way, we should take time to consider the rural evidence, illustrated here by the studies of supposedly ‘isolated’ rural places like Jämtland in Sweden by Olof Holm and South Uist in the Western Isles of Scotland by Niall Sharples et al.

This entails looking at the evidence from the more circumstantial end of the spectrum, such as the grave goods linked to trade and bullion-based transactions looked at by Holm for Jämtland. According to Holm’s model, rural locals brought not only market goods back from their regular visits to nodal markets like Birka, but also market practice.

As I noted in my Routledge book, A Viking Market Kingdom, ‘Holm’s analysis of grave goods indicate commerce and bullion was well known, inclusive of the ‘middle classes’, and especially among the farming community. Burials with scales, standardized weights (mainly oblate-spheroids), hacksilver and coin (in 1/3 to ½ of male graves) are paralleled with graves in Birka, suggesting these ostensibly isolated rural inhabitants traded and made payments with silver like their town-based peers (Holm 2015: 85-91)’.

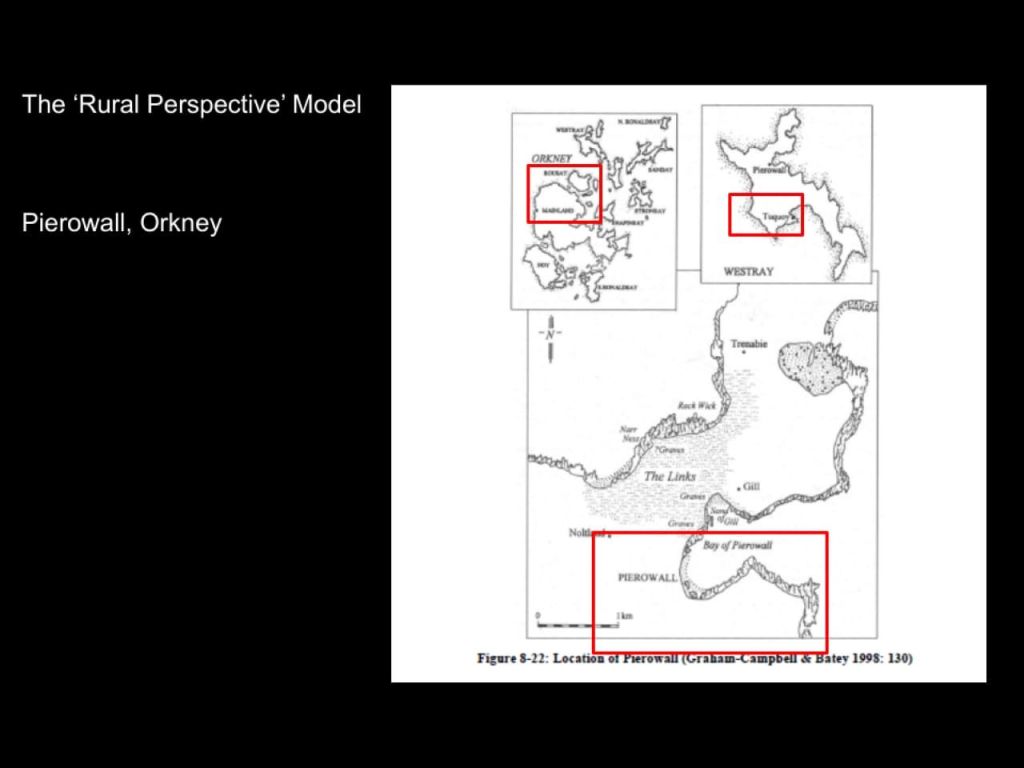

© Graham-Campbell & Batey 1998: 130

If we apply Holm’s model to rural Scandinavian Scotland (Scandinavian Scotland was essentially entirely rural, but you take my point), we can look beyond – important and interesting – speculation about the presence of Sandtorg-type coastal markets at sites like the natural harbour at Pierowall Bay on Orkney and, instead, look to the import-rich burials clustered around it to imagine scenarios whereby the locals traded commercially within their local and regional communities throughout the year, having been introduced to the practice by a combination of trade coming to their area and individuals and trading collectives travelling to markets that were part of wider economic networks.

In Scotland, my own contributions to publications for Bornish [Bornais] on South Uist in the Western Isles, and Colleen Batey and my own contributions for the Earl’s Bu, Orkney, demonstrate that – even into that ‘Late Norse’ post-1050 period – sites that were seemingly isolated from networked nodal markets were au fait with the type of bullion currency and corresponding weights that seems to have facilitated network trade across the Scandinavian world.

In the case of Bornish and the Earl’s Bu, the evidence is the presence of both oblate-spheroid type standardized weights in Late Norse contexts (of the type seen at sites like Torksey), but the metrological equipment from the far earlier Viking-Age Kiloran Bay boat burial – dated by James Graham-Campbell to the 870s – suggests real and long-lasting economic agency in the Scottish islands across the Scandinavian period.

Moreover, as the last image suggests, the 870s parallels between two insular Scottish Scandinavian sites at Kiloran Bay and Talnotrie, the latter in Galloway near to the Galloway Hoard site, and a site like the winter-camp at Torksey in Lincolnshire indicate the rapid spread of market practice – inclusive of bullion currency use – throughout Scandinavian economic networks.

Economic Networks

While I and others like Søren Sindbæk have argued – correctly, I think – for the Seven Degrees of Separation-type models that see the farm producer connected, ultimately, to the ruler of a network kingdom (i.e., one based on interest in and attempted influence over trade networks, as suggested by Blomkvist), it seems logical to base our understanding of normal, day-to-day, economic activity on the small trades made between that farmer (of land and/or sea) and their immediate neighbours.

Now, while we may have lost the evidence for those economic trades that might be thought of as commodity-for-commodity barter, we can see from areas like Jämtland and western Scandinavian Scotland that seemingly isolated farms and settlers knew how to, and likely did, trade in the manner of the more traditional trading sites. Although it seems probable that the majority of the bullion economy type weights and long-distance trade goods were acquired in seasonal visits to markets and via visits of network traders to temporary beach markets (vel sim), the latter would need to be redistributed (aided by the former used to weigh bullion currency) in the dispersed rural homeland.

Consequently, did the one visit to a Kaupang or a Dublin outweigh the subsequent cascade of smaller, local transactions as the trade goods acquired at these sites spread into the hamlets and villages and thence into their hinterlands? I think the answer is as nuanced as our collective understanding of the field we are discussing this week: both types of trade are necessary for the whole to work, but the number of ‘cascade’ transactions in rural settings must have been greater – and certainly more transformative – than those within the more permanent market sites.

This aspect alludes to the importance of understanding economic networks on multiple levels and not merely those impressive long-distance lines we all like to draw on maps; rather, I am interested in those economic networks that existed when the villagers tasked with the seasonal visits to the temporary or permanent market sites returned to their rural communities and began the process of cascading both the goods and knowledge of the more efficient (i.e., commercial) ways of exchanging them throughout the local communities.

Of course, this was a two-way street: the transactional knowledge and local economic networks that this process created was a reflection of those local communities having trade goods in which the wider market networks were interested, whether commodities like furs, slaves, tar or whetstones, and which created circuits of trade from the seemingly isolated farmer to the ruler of Birka or Dublin.

To reiterate: all of this is not to say that the large(r), regularised and regulated economic sites or markets and the impressive long-distance networks aren’t equally or even more important than the micro scenarios sketched out here. Rather, it is one of those occasional reminders that, quite naturally and logically, we tend to favour those economic sites and networks that have obvious and deeply stratified archaeological evidence or even historical attestations for their existence.

The discovery of new littoral or beach trading market sites in areas where we previously had none are important – I think here of the potential evidence for dirham-using beach markets at Stevenson Sands, Ardeer, on the Irish Sea Ayrshire coast of Scotland, and on the Isle of Man (Alison Fox [pers. comm.]; Bornholdt Collins 2024), in addition to the aforementioned Sandtorg trading and boat-repair site in the Arctic Troms region of Norway. Similarly, the discovery of new overwintering camps like the Coquet Valley site in Northumbria can open up entirely new historical perspectives and interrogate the existing market-camp dataset.

However, what their discovery is doing is demonstrating more of the same: i.e., more of those market sites (or sites where market activity took place on a regular basis) where many individuals are drawn to trade in town-like conditions. While these are vital parts of the still-emergent dataset relating to markets, I think collectives like ours have a duty to think about those areas about which we know least but are – as the above rural sites suggest – loaded with possibility.

What the still quite new Scottish Scandinavia and Jämtland evidence might (and only might) suggest, however, is that we should take a step back by taking a step closer: real illumination for what probably constituted the bulk of economic transactions requires the family farm-level or ‘village shop’ perspective, and it might well be those rural graves and hacksilver hoards that tell the story of how most of the Viking-Age Scandinavian world experienced economic networks and economic sites.

The End

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/legalcode.en

Leave a comment