‘Didja hear the news about good old General Mercer?’ The Letters and Lyrics of Hugh Mercer, George Washington, and Lin-Manuel Miranda

This blog focuses on those primary sources that are accessible via the internet, including written correspondence involving George Washington, in an attempt to tell the story of Scots-born American Revolutionary, Hugh Mercer. In particular, it looks at his relationship with the Founding Fathers, and investigates his role in the critical actions of 1776 and January 1777. It also acknowledges the continuing popular interest in Mercer, most recently demonstrated in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton: An American Musical.

It is hoped that future research will investigate further this posthumous existence of Mercer and, in particular, the object biography [i.e., history] of his sword, which is to be loaned/donated to the Museum of the American Revolution by the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia. The museum opened on April 19th, 2017, but some of its collections, although not yet Mercer’s sword, can already be viewed online.

My First Blog: What the Internet Taught Me About Hugh Mercer

In 2015, I wrote my first piece on Hugh Mercer, a blog that concentrated on his early life in Scotland and his life on the run in America after Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Jacobite army, in which he had served in a medical role, was defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

Read about his life on the Pennsylvanian frontier and his adventures during the French and Indian War, in which he befriended a young George Washington, whom he followed to Fredericksburg in Virginia before becoming one of the early heroes of the American Revolution.

Mercer’s Sword Presented to Museum of the American Revolution

On the 240th anniversary of Mercer’s death, the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia presented the Museum of the American Revolution with his sword.

Online Research and the American Revolution

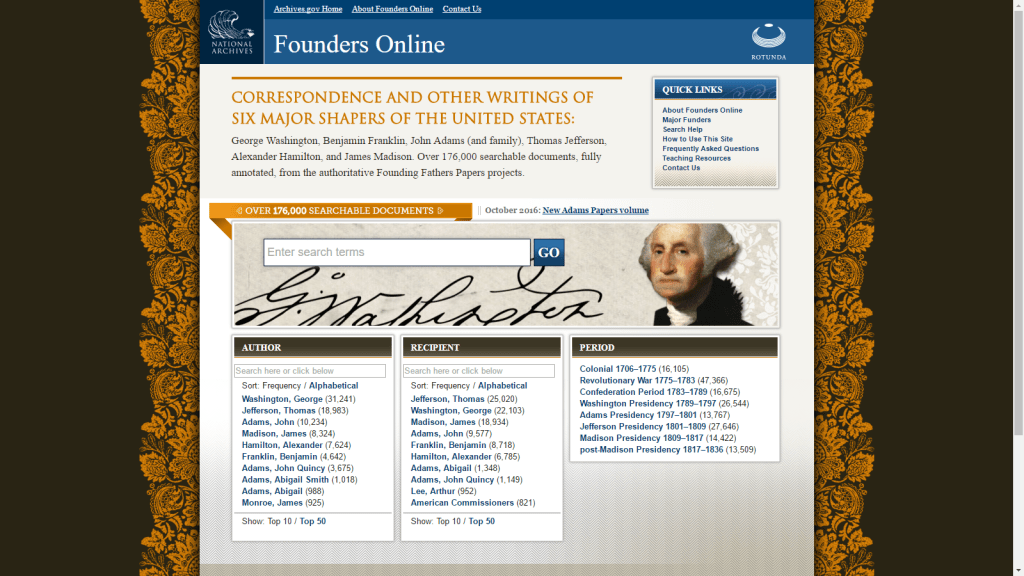

As the title, and that of my previous blog – What the Internet Taught Me About Hugh Mercer – suggest, I am interested in exploring the possibilities of online research as it relates to the American Revolution. Being UK-based, this method was, initially, a case of pragmatism in the face of a lack of access to source material, but the high quality of online information I have discovered in the process (e.g., Founders Online) has demonstrated its utility.

I am fascinated by the Scottish connections (relating to both birth and descent) to 18th-century war and society in North America, and, in particular, the disproportionately-prominent role of Scottish – or, like Dr. Benjamin Rush, Scottish-trained – medical doctors in the leadership of the American Revolution.

In 2016, I was fortunate enough to be able to visit sites, and see artifacts, related to Mercer, including his original resting place at Christ Church, and his current one, at Laurel Hill Cemetery.

Methods and Sources

Many letters and orders relating to Mercer can be accessed via the internet, courtesy of Founders Online, a wonderful project between the (US) National Archives’ National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the University of Virginia Press.

Mercer also appears in several publications, such as a contemporary diary or a posthumous oration, that have been archived on Archive.org. The most pertinent of these are W.B. Reed’s Oration (1840), and J.T. Goolrick’s Life of Mercer (1906). While their accuracy is at times uncertain, at least relative to the sources in Founders Online, some of the references made can be corroborated by reference to original correspondence.

The extracts made available (with permissions from the publishers) in Google Books are also of help to the long-distance researcher. In this regard, Whitfield Jenks Bell’s chapter on Mercer in ‘Patriot Improvers: 1743-1768‘ (1997) is, for example, particularly useful for adding references to Mercer’s early life in Scotland.

That said, it was felt that this blog should focus on those transcripts of primary sources available on the internet, with a bias towards Founders Online, so as not to (i) replicate my first blog on the subject any more than is necessary to contextualize the sources, and, (ii), prioritize sources verified by the US National Archives and the University of Virginia Press.

Who was Hugh Mercer?

Scottish Background

Most, if not all, internet pages state that Mercer was born in Aberdeenshire in 1726 and studied at Marischal College in Aberdeen, but I am grateful to Jenks Bell (1997: 447) for providing some footnotes, which will allow for future offline source verification. For the record, Jenks Bell cites ‘Hew Scott, Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae, VI (1926), 235′ for the details of Mercer’s birth, and ‘Peter J. Anderson, comp., Fasti Academiae Mariscallanae Aberdonenis (Aberdeen, 1898), II, 315′ for Mercer’s attendance at Marischal.

Scott’s FES VI is on Archive.org, containing the biographical entry (p.235) for Hugh’s father, William, the minister for Pitsligo parish. Anderson’s Fasti Academiae is also on Archive.org, and it lists a ‘Hugo Mercer’, which appears – I may misread – to be listed under 1741 ‘Alumni and Graduates in Arts’.

As is the case above in relation to Mercer’s upbringing, most online sources will add that Mercer fled Scotland for Pennsylvania in c.1747 subsequent to the defeat of Charles Edward Stuart’s Jacobite forces at the Battle of Culloden in April 1746, a battle in which Mercer apparently served as an (assistant?) surgeon. It is not clear when (if?) Mercer received formal medical training, but a best guess would place it in Aberdeen and, this being pure speculation on my part, with a mentor in the Jacobite army.

Update: Correspondence with Samuel K. Fore suggests that – to date – nothing can be confirmed about Mercer in relation to any medical training, with Fore’s source being archival research undertaken by the University of Aberdeen.

The American Colonies

Once in the American colonies, Mercer’s biography becomes clearer, and it is certain that (while seemingly established as a frontier doctor in western Pennsylvania) he volunteered to fight in the ‘French and Indian War’ (the name given to the Seven Years’ War [1754-63] between Great Britain and France [and their proxies] in North America). Years later, he would volunteer again as a Patriot against the Crown in the Revolutionary War, leaving his apothecary in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he had moved to after leaving Pennsylvania.

Mercer’s Service in the French and Indian War

Mercer served with George Washington in both American conflicts, with the earliest known correspondence between the pair (or from Washington to whoever was in charge at the camp that day) dating to September 9th, 1758, when Mercer was a Lieutenant Colonel.

As will be seen in a later section, this colonial service stood Mercer in good stead for promotion during the Revolution. Caveat: this letter is not wildly exciting, unless you like logistics, in which case it is.

‘To Lieutt Colo. Mercer of Pensylvania or Officer Commanding at Rays Town

‘Sir Camp at Fort Cumberland 9th Septr 1758.

‘I this moment receivd notice from the Commissary, that only three day’s Flour remaind upon hand for the Troops at this Incampment. Mr Hoops is wrote to on the occasion, and I must beg the favour of you to facilitate any measures he shall propose to supply us in time; by affording an Escort &ca—Not knowing how soon we may be orderd to join you, I can’t tell how much Provisions is wanted—possibly ten days will serve till the Generals pleasure be known. We have no Waggon’s at this place, otherwise I wou’d have given you no trouble in this affair. I am Sir Yr Most Obedt Hble Servt

Go: Washington’

Reference: “From George Washington to Hugh Mercer, 9 September 1758,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified October 5, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-06-02-0004. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 6, 4 September 1758 – 26 December 1760, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, p. 6.]

We know that Mercer was well thought of during this conflict, being the recipient of a medal for the September 1756 Kittanning/Armstrong Expedition. The Heinz History Centre tells us that, two years later, he was given the command of what would be called Fort Mercer (situated next to the subsequent Fort Pitt in the newly-anointed ‘Pittsburgh’) after the successful Forbes Expedition of 1758, and was mentioned by name by Sir Jeffrey Amherst, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America:

‘Some such men as Col Mercer amongst the Provincials would be of great Service…’

Reference: http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/hugh-mercer/

Mercer’s Character

But what of his character? What would Mercer have been like to meet? I used the following excerpt in my previous blog, but I feel it is important to repeat it as it gives the reader an insight into Mercer’s personality. Via Jenks Bell’s ‘Patriot Improvers’, we have access to a wonderful primary source, namely a letter written on May 23rd, 1759, by Mercer to fellow Scot, James Burd. Written in reply to a request that his troops be allowed to visit the nearest population centers, Mercer’s tone suggests that he had a wry sense of humor, even when in the midst of the demanding task of constructing and defending the fort:

‘My Opinion as to their going to the Settlement you shall have with all the freedom in life: I never knew any other Advantage accruing to Soldiers, I mean ours, from being in Towns on the frontier, than black eyes, Claps, & eternal flogging; and unless Carlisle & Shippensbg are of late miraculously altered in the point of Morals, the old game at either of these seats of Virtue & good manners would undoubtedly be play’d over; especially as it is intended that the men should receive their Pay there, to enable them, more and more, besides having their pockets pick’d by Tavern keepers.’

References: Patriot Improvers, 1743-1768 (Jenks Bell 1997: 449), via Shippen Papers, IV, 39 (HSP = Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Mercer and George Washington: From Pennsylvania to Virginia

Between the two American wars, Mercer moved from Pennsylvania to Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he established a medical practice (his apothecary is now a museum where one can see Mercer’s Kittanning Medal), counting Mary Ball Washington, George Washington’s mother, among his patients.

It can be stated that Mercer and George Washington knew each other well via their shared military service, membership of Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No.4, and business, such as Washington’s sale of Ferry Farm to Mercer (a rather drawn-out transaction, which can be followed over several letters accessible via Founders Online).

As will be seen below, Mercer’s good character and the respect for his abilities also shine through the online primary sources, with Charles Lee and Washington both speaking highly of the Scot.

Recently, this fine reputation has been burnished, this time in a successful musical:

“Good old General Mercer” – Hugh Mercer in ‘Hamilton: An American Musical’

Although one of the more obscure figures of the Revolution, most likely due to his death relatively early in the war, interest in Mercer has increased in recent years. Indeed, Mercer is name-checked in ‘The Room Where it Happened’, a song in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton: An American Musical:

‘[BURR]

Ah, Mister Secretary

[HAMILTON]

Mister Burr, sir

[BURR]

Didja hear the news about good old General Mercer?

[HAMILTON]

No

[BURR]

You know Clermont Street?

[HAMILTON]

Yeah

[BURR]

They renamed it after him. The Mercer legacy is secure

[HAMILTON]

Sure

[BURR]

And all he had to do was die

[HAMILTON]

That’s a lot less work

[BURR]

We oughta give it a try’

Source: http://genius.com/Lin-manuel-miranda-the-room-where-it-happens-lyrics

On Genius.com, Miranda explains how Mercer came to be included:

‘I questioned: was there Mercer street in 1780? So I looked it up, and saw that it used to be Claremont Street.

‘So then who was Mercer named after? It was some general who died two years into the war.

‘What’s funny is how the two of them were obsessed with their legacies. So that’s one of those things where the line actually led me to a really cool historical story and away into the tune. So sometimes you’re working the rhyme to fit the circumstances, but sometimes the line leads you somewhere you don’t expect.’

Source: http://genius.com/8093199

Why Blog?

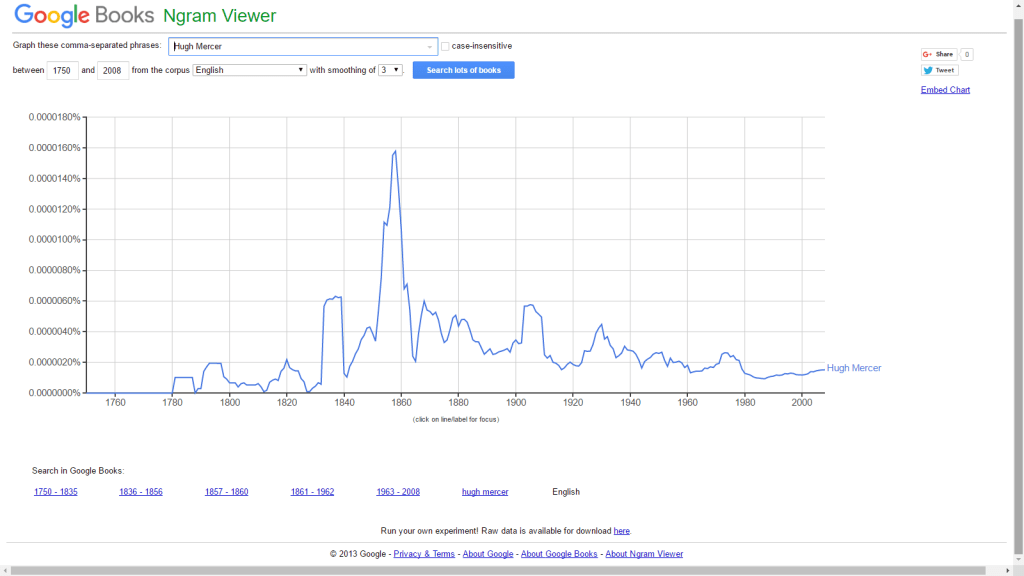

Despite more recent interest in Mercer, he is still neglected in relation to his impact; in my opinion, at least. The following screen-grab shows the mentions of ‘Hugh Mercer’ in those texts to which Google has access. The major caveat, however, is that one of Hugh Mercer’s sons was also named Hugh Mercer (1776-1853) (he features regularly in Founders Online due to his award of a paid-for education by the newly-formed United States); and a relatively prominent grandson was Hugh Weedon Mercer (1808-1877).

While it is possible to look at each reference Google provides, I’ll spare myself and the reader any further analysis beyond the fact that this is an interesting way to represent the waxing and waning of interest in a public figure.

Although this lack of recognition is, arguably, unwarranted, I would not have returned to the subject (excepting the Mercer Sword) without new information. Of the two sources, one is a verified letter, and the other is a report of an alleged letter in a secondary work.

The Washington-Reed Letter

The former is a letter by Washington to Joseph Reed concerning Mercer’s health after the Battle of Princeton. I first became aware of this letter via a footnote (pg. 38) in W.B. Reed’s 1840 panegyric, ‘Oration Delivered on the Occasion on the Reinternment of the Remains of General Hugh Mercer Before the St. Andrew’s and Thistle Society’, a publication I had been made aware of by James (Jim) Bishop of the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia.

W.B. Reed’s work seems to be a transcript of his speech made on November 26th, 1840, to mark the translation of Mercer’s remains within Philadelphia from a plot (that had become prone to flooding) at Christ Church to Laurel Hill. Fortunately for my internet methodology, I was able to access archive.org’s online version of the Oration.

Mercer and the Crossing of the Delaware River

The unverified source is merely a report of a letter (there is no transcript) in W.B. Reed’s Oration. This source suggests Mercer – in his position of Brigadier General and in alliance with George Washington’s aide-de-camp, Joseph Reed – had a major role in the momentous decision to attempt the crossing of the Delaware River during the night of 25/6th December 1776, a tactical maneuver that may have saved the Revolution. The letter is purported to have been written by Mercer’s own aide-de-camp, John Armstrong, Jr.

These accounts alone would have sufficed, but as my researched continued, I realized that other correspondence and written accounts helped create a fuller picture not only of Mercer, but also of the key events of the in which he was involved during the first months of the Revolution and the pivotal winter of 1776/7.

Mercer and the American Revolution: Key Developments

Having (possibly) seen battle at Culloden, and definitely gained experience of conflict during the 1750s, Mercer appears to have been keen to help his adopted land once it became clear in 1774/5 that British and Colonial positions were entrenched to the extent that both sides preferred conflict to peace.

Key Development: Williamsburg Gunpowder, April 1775

The first ‘Revolutionary’ correspondence relating to Mercer that I can find on Founders Online is dated April 26th, 1775, and comes in the form of a letter written by him, George Weedon (a fellow mason from the same lodge), Alexander Spotswood, and John Willis. It references one of the (most famous) instances of the British authorities’ tactic of removing gunpowder from local magazines – the Williamsburg ‘Gunpowder Incident‘ – in order to prevent it falling into the hands of potential or actual rebels against the Crown:

‘Sir Fredericksbg April 26th 1775

‘By intelligence from Williamsburg it appears that Capt. Collins of his Majestys Navy at the head of 15 Marines carried off the Powder from the Magazine in that City on the night of Thursday last and conveyed it on board his Vessell by Order of the Governor. The Gentlemen of the Independant Company of this Town think this first Publick insult is not to be tamely submitted to and determine with your approbation to join any other bodies of armed Men who are willing to appear in support of the honour of Virginia as well as to secure the Military Stores yet remaining in the Magazine. It is proposed to March from hence on Saturday next for Williamsburg properly accoutred as Light Horsemen.

‘Expresses are sent off to inform the Commanding Officers of Companies in the adjacent Counties of this our Resolution & we shall wait prepared for your Instructions & their assistance. We are Sir Your humble Servants

‘Hugh Mercer

G. Weedon

Alexander Spotswood

John Willis

‘As we are not sufficiently supplied with Powder, it may be proper to request of the Gentlemen who join us from Fairfax or Prince William, to come provided with an over portion of that Article.’

Reference: “To George Washington from Spotsylvania Independent Company, 26 April 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified October 5, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-10-02-0271. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 10, 21 March 1774 – 15 June 1775, ed. W. W. Abbot and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995, pp. 346–347.]

I note here that W.B. Reed (1840: 17) also includes a transcript of the above letter, adding credence (in the sense that he accessed original documents) to some, but not all, of his assertions.

Key Development: From Colonel to Brigadier General

On June 7th, 1776, Mercer was promoted from his Colonelcy with the 3rd Virginian Regiment to the position of Brigadier General, a fact alluded to by George Washington in this extract from a letter to John Hancock:

‘Yesterday I sent off an Express to Genl Mercer with Orders to set out directly for Head Quarters, and at the same time enclosed his Commission’

Reference: “To George Washington from John Hancock, 7 June 1776,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified October 5, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0361. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 4, 1 April 1776 – 15 June 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991, pp. 453–455.]

Summer of 1776: Mercer in High Regard

There seems to have been an impression among the senior American military hierarchy, like Charles Lee, that Mercer was a safe pair of hands and extremely capable:

Major General Charles Lee’s Opinion of Mercer, April 5th, 1776:

‘My Dr General Williamsburg April the 5th 1776

‘[…] My Dr General, crown yourself with glory and establish the liberties and lustre of your Country on a foundation more permanent than the Capitol Rock—my situation is just as I expected. I am afraid that I shall make a shabby figure without any real demerits of my own —I am like a Dog in a dancing school—I know not where to turn myself, where to fix myself—the circumstances of the Country intersected by navigable rivers, the uncertainty of the Enemy’s designs and motions who can fly in an instant to any spot They chuse with their canvass wings throw me, or wou’d throw Julius Cæsar into this inevitable dilemma—I may possibly be in the North, when as Richard says, I shou’d serve my Sovereign in the West—I can only act from surmise and have a very good chance of surmising wrong—I am sorry to grate your ears with a truth, but must at all events assure you, that the Provincial Congress of N. York are Angels of decision when compar’d with your Countrymen the Committee of Safety assembled at Williamsburg. Page, Lee, Mercer and Payne are indeed exceptions, but from Pendleton, Bland the Treasurer & Co.—libera nos Domine […]’

Reference: “To George Washington from Major General Charles Lee, 5 April 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0031. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 4, 1 April 1776 – 15 June 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991, pp. 42–45.]

George Washington’s Opinion of Mercer

This positive impression was certainly shared by Washington, who supported Mercer despite the latter being a ‘Scotchman’ (ref.) when many of his countrymen from the land of his birth were conspicuous for their loyalty to the Crown. As a result, some important Revolutionaries were suspicious of Scots-born Americans. The following extract is from a letter written by Washington to his brother John on March 31st, 1776:

‘[…] General Lee, I expect, is with you before this—He is the first Officer in Military knowledge and experience we have in the whole Army—He is zealously attachd to the Cause—honest, and well meaning, but rather fickle & violent I fear in his temper however as he possesses an uncommon share of good Sense and Spirit I congratulate my Countrymen upon his appointment to that Department. The appointment of Lewis I think was also judicious, for notwithstanding the odium thrown upon his Conduct at the Kanhawa I always look’d upon him as a Man of Spirit and a good Officer—his experience is equal to any one we have. Colo. Mercer would have supplied the place well but I question (as a Scotchman) whether it would have gone glibly down. […]’

Reference: “From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, 31 March 1776,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-03-02-0429. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 3, 1 January 1776 – 31 March 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, pp. 566–571.]

On July 4th, 1776, Washington can be seen approving of Mercer’s activities in ‘New Ark’ (modern Newark), as part of the campaign in New York and New Jersey:

Washington continued to speak highly of Mercer in the following days, recommending him to Brigadier General William Livingston on July 5th:

‘[…] Since this Letter was begun another of your Favours came to my Hands informing me that the Enemy have thrown up two small Breast Works on the Cause way from the Point. You also request some experienced Officers to be sent over—which I would gladly comply with if in my Power but I have few of that Character, & those are so necessarily engaged here, that for the present I must refer you to Genl Mercer whose Judgment & Experience may be depended on. I have wrote him that I should endeavour to send over an Engineer as soon as possible. […]’

Reference: “From George Washington to Brigadier General William Livingston, 5 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0149. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 213–215.]

In his online biography, Samuel K. Fore includes Washington’s recommendation of Mercer, made in another letter to Livingston, this time from July 6th, 1776:

‘…in his Experience and Judgement you may repose great Confidence’

Reference: Samuel K. Fore, “Hugh Mercer,” The Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington, accessed October 26, 2016, http://www.mountvernon.org/digital-encyclopedia/article/hugh-mercer/.

The recipient of Washington’s letters was William Livingston, Brigadier General in the New Jersey militia since October 1775, who would be elected as the first non-royal Governor on August 31, 1776. (As his name suggests, the American-born Livingston was of Scottish descent, his grandfather, Robert Livingston the Elder, having been born in Roxburgh, Scotland). A transcript of Washington’s letter, dated July 6th, 1776, can be read here at Founders Online.

William Woodford’s Opinion of Mercer

Even those who, like the William Woodford, were passed over for promotion from Colonel to Brigadier General, could not find it in themselves to criticize Mercer. Here, Woodford writes to Washington on July 6th to query his failure to be promoted:

‘[…] I am sorry to trouble you with complaints, but give me leave Sir to say I feel myself much hurt by the late promotion of my very worthy friend Col. Mercer, and to request your patience to hear my reasons in the best manner I am capable of giving them, with that freedom, which I flatter myself will not be taken amiss by you […]

‘When the Honorable, the Congress, took out troops upon the Continental Establishment, a few months ago, I again expressed my wish that Colonel Mercer might be appointed to a higher office, their wisdom directed them to make the arrangement otherways, and I looked upon the army as firmly established in such a manner, that every officer would rise in his turn, unless some fault could be laid to his charge. I have the same good opinion of that gentleman I ever had, but what I complain of is the impropriety as I conceive of the appointment, and that the promotion of an officer at that time serving under me, (however well he may deserve it) reflected dishonor upon myself, and will be attributed by the world to some misconduct in me, or at best inability to fill a higher office.’

Reference: “To George Washington from Colonel William Woodford, 6 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0160. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 228–230.]

Washington’s reply (July 30th, 1776) gives us the probable reason for Mercer’s advancement, namely his service at a higher rank in the French and Indian War:

‘[…] I am sorry you should consider Genl Mercer’s late appointment as a slight put upon your services, because I am persuaded no slight was intended.—Whilst the service was local, and appointment of Officers affected no other Colony than that in which they were raised, the Continental Congress discovered no inclination to interpose in the appointments, But when they were to be chosen for more extensive service each member then concieved his own Colony to be affected, and that it was his duty to make choice of Gentlemen for Genl Officers whose former Rank (as they were to be placed over Officers that have commanded Regiments since the commencement of these disputes, and many of the field Officers in the last war) would give them the best pretensions, and those over whom they were to be placed, least offence—Upon this principle therefore I knew it was that Genl Mercer got appointed, and upon this principle also it will be that Col Stephens is, if such a event should take place; upon a revision therefore of the matter I cannot think you will find any just cause of complaint notwithstanding you stood foremost in the appointments of Virginia; which, as I observed before, were local, and whilst they regarded no other Colony, were unattended to by the Congress; but you should consider that Col Mercer, Genl Lewis, and Col Stephens were Field Officers in the same service, and at the same time, that you acted as subaltern, and that in general appointments by the Congress, regard must be had to the troops here, as much as elsewhere, the Officers being equally tenacious of Rank; and only reconcilable to Mercer’s coming in over them on acct of his former Rank in the army.’

Reference: “From George Washington to Colonel William Woodford, 30 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0388. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 523–524.]

John Adam’s Opinion of Mercer

Washington’s explanation to Woodford is echoed by John Adams in a letter to Daniel Hitchcock, sent on August 3rd, 1776:

‘[…] Mercer, Lewis, More, and How, were not only Men of Fortune, and Figure, in their Countries, and in civil Imployments, but they were all, veteran Soldiers, and had been Collonells, in a former War.[…]’

Reference: “From John Adams to Daniel Hitchcock, 3 August 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0190. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 4, February–August 1776, ed. Robert J. Taylor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979, pp. 427–430.]

However, despite the confidence in Mercer’s ability and his consequent personal advancement, the outlook for the Revolution looked increasingly bleak as 1776 passed, culminating in what Paine would call ‘the American Crisis’.

Winter 1776/77: Revolution in Jeopardy

This was the period that, as the Revolutionary Thomas Paine noted in his first pamphlet of The [American] Crisis (published in December 1776), ‘[tried] men’s souls’.

Although not proven (see this article by Jett Conner on All Things Liberty), it has become tradition that this piece was read to the American Continental Army on December 23rd, i.e., a few days prior to the crossing of the Delaware (December 25/6th) that preceded the first attack on Trenton (December 26th, see below). This was at a time when we know from correspondence that Washington and his commanders were faced with the prospect of a number of their soldiers returning home for winter, threatening the revolution in the process. Thus, the opening line of Crisis was pointed:

‘These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country…’

Notes: via ‘The Great Works of Thomas Paine. Complete. Political and Theological‘.

Realizing the range of primary sources relating to the winter of 1776/7 available online, I decided to look beyond W.B. Reed and include pertinent works like Paine’s and the entries of Philadelphia diarist Christopher Marshall. Reed, however, remained of interest, not least for a letter (quoted below) he claims to have received from John Armstrong, Jr. (d. 1843), who had been Mercer’s aide, and which – if genuine – gives a fascinating insight into Mercer’s role in the lead-up to the crossing(s) of the Delaware River to New Jersey and the subsequent engagements at Trenton and Princeton.

The following provides the briefest of outlines to the military situation in the winter of 1776/7, after an aside on the Scottish element in Washington’s command.

December 14th, 1776: The Last Communique and the Scottish Connection

The last written communication from Washington available via Founders Online is this order sent to James Ewing, Mercer, Adam Stephen, and Lord Stirling on December 14th, 1776. We note here that Scottish links and other similarities to Mercer were strong in this group: Ewing was Pennsylvania-born, but of (Ulster) Scots / Scots-Irish descent, and, like Mercer, had served in the Pennsylvania militia during the 1750s. Adam Stephen was, like Mercer, a Scots medic and military man who had studied in Aberdeen (as, seemingly, Mercer) and emigrated to America. Finally, ‘Lord Stirling’ was William Alexander, whose father James Alexander had fled his native Scotland after the failure of the first Jacobite rebellion in 1715/16, thus perhaps sharing similarities with Mercer’s supposed flight after the second Jacobite rebellion of 1745/6 and the Battle of Culloden.

War in Winter: 1776/7

Having been forced out of New York and New Jersey, the Continental Army had looked like starting the year 1777 facing the very real prospect of defeat, as Washington’s letter to his brother on December 18th, 1776, quoted in W.B. Reed (1840: 28), suggested:

‘I have no doubt but General Howe will still make an attempt on Philadelphia this winter. I see nothing to prevent him a fortnight hence, as the time of all the troops except those of Virginia, now reduced almost to nothing, and Smallwood’s regiment of Marylanders, equally as low, will expire before the end of that time. In a word, if every nerve is not strained to recruit the new army with all possible expedition, I think the game is nearly up. You can form no idea of the perplexity of my situation. No man ever had a greater choice of difficulties, and less means to extricate himself from them. But under a full persuasion of the justice of our cause, I cannot contain the idea that it will finally sink, though it may remain for some time under a cloud.’

However, the bold decision to cross the Delaware River from Pennsylvania to New Jersey on the night of 25/26th December returned the initiative to the Revolutionaries.

Mercer and the Crossing of the Delaware (25/6th December)

In relation to the decision-making process behind the decision, W.B. Reed claimed (1840: 29-30) that he had received a letter from the (c.82-year-old) John Armstrong, Jr. (1758-1843), who had been Mercer’s aide-de-camp. W.B. Reed (1840: 29–30) wrote:

‘As early as the 14th December the idea of an attack seems to have suggested itself to the mind of the Commander in Chief, but to have been dependent on a junction with General Lee, then supposed to be in the rear of the enemy, but who was really their prisoner. A living witness*, in a letter written to me within a few days, thus describes this movement: “Two or three days after we had crossed the Delaware there were several meetings between the Adjutant General and General Mercer, at which I was permitted to be present; the questions were discussed whether the propriety and practicability did not exist of carrying the outposts of the enemy, and not ought to be attempted. On this point no disagreement existed between the generals, and to remove objections in other quarters it was determined they should separately open the subject to the Commander in Chief, and to such officers as would probably compose his council of war, if any should be called. I am sure the first of these meetings was at least ten days before the attack on Trenton was made’

‘*General, then Major, Armstrong, then an aide of General Mercer’.

Notes: The crossing of the Delaware referred to above is the initial crossing made into Pennsylvania by the Americans fleeing the British in New Jersey, not the famous crossing on December 25/6th. As far as I can tell, the ‘Adjutant General’ was Colonel Joseph Reed, Washington’s own aide-de-camp who, coincidentally, was (re)buried in the same Laurel Hill Cemetery in which Mercer now reposes. The Commander-in-Chief was, of course, George Washington.

In terms of the authenticity of the letter, W.B. Reed’s use of primary sources that can be collaborated leads me to believe – although it is only my opinion – that he probably did enter into correspondence with John Armstrong. Jr. (whose father – John Armstrong, Sr. – had, incidentally, served with Mercer at the Kittanning Expedition in 1756).

Of interest here is the suggestion that Mercer and (presuming I am correct in my identification) Joseph Reed were instrumental in either suggesting the attack on Trenton to Washington, and had done so by c.December 15/16th, at the latest, or – perhaps more likely? – in backing Washington’s own plans to cross the Delaware River. I would love to know more about this critical decision; it is at junctures such as this one that the limitations of internet research become apparent.

Perhaps relevant is Washington’s aforementioned General Orders of December 14th, 1776, sent to ‘Brigadier Generals James Ewing, Hugh Mercer, Adam Stephen, and Lord Stirling’, which are defensive in nature, and include preparations for an orderly retreat to Philadelphia, should the British be successful in an amphibious assault:

‘I would advise you xamine the wh River […] and after forming an Opinion of the most profitable Crossing places, have those well watched, and direct the Regiments or Companies most Convenient to repair as they Can be formed, immediately to the point of attack, and give the Emy all the Opposition they possibly Can’

Reference: “From George Washington to Brigadier Generals James Ewing, Hugh Mercer, Adam Stephen, and Lord Stirling, 14 December 1776,”Founders Online, National Archives, last modified October 5, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0264. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 7, 21 October 1776–5 January 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997, pp. 331–333.]

Whether Mercer and Joseph Reed had as much influence as is suggested by the reported letter of Armstrong. Jr. in a hagiographical account presumably designed to show Mercer in the best light, W.B. Reed (1840: 30) adds that, according to the diary of Christopher Marshall (1709-1797), news of an impending attack across the Delaware was doing the rounds in Philadelphia on December 18th:

‘Great numbers of country militia coming in to join General Washington’s army. News that our army intend to cross at Trenton into the Jerseys’

Notes: Pg. 122. Christopher Marshall’s diary is available here on Archive.org

It should be noted that, although the plan was not his, Mercer had worked on an (I think abortive) plan for an amphibious night landing on Staten Island that July (cf. W.B. Reed [1840: 22]), so he would have been aware of the basic (if non-winter) logistics behind such an undertaking:

‘[…] The Plan of Attack which I propose is as follows.

‘To Ferry over between the Hours of 11 & 2 in the Morning to morrow Night—from Thompsons Creek to the Woods where the Marsh is most practicable 1400 Men. —Col. Brodhead with 400 P. Riflemen to pass over first & take possession of the Ground where the Creek forms the Neck of smallest width—there to lye in Ambush from Creek to Creek […]

‘[…] We propose if Successfull to retire by the Blazing Starr—for this purpose not only the Craft we cross over in from Thompson Creek but all others that can be collected along the Shores, will be collected there by the Parties stationed at our different Posts near that Place

‘I shall have that Number of militia prepared on this Quarter, without weakening too much the Several Posts we occupy on the Jersey Shore—I shall endeavour to procure Guides for the Several Parties—Your Instructions for the improvement of the Above plan will give great pleasure—& may ensure its Success. […]’

Reference: “To George Washington from Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, 16 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified December 6, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0253. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 344–347.]

The Battles of Trenton (December 26th, 1776) & Assunpink Creek (January 2nd, 1777)

In any case, once across, the Americans defeated (mainly Hessian mercenary) Regulars at the Battle of Trenton (December 26th). We know of Mercer’s instructions via the General Orders, dated December 25th, from Washington to his commanders:

‘General Stevenss Brigade to form the advanced party…General Stevens is to attack and force the enemies Guards and seize such posts as may prevent them from forming in the streets and in case they are annoy’d from the houses to set them on fire. The Brigades of Mercer & Lord Stirling under the command of Major General Greene to support General Stevens, this is the second division or left wing of the Army and to march by the way of the Pennington Road…

‘General Stevens Brigade with the detachment of Artillery men to embark first, General Mercers next; Lord Stirlings next, Genl Fermoys next who will march in the rear of the second division and file off from the Pennington to the Princeton Road in such direction that he can with the greatest ease & safety secure the passes between Princeton & Trenton…’

Reference: “General Orders, 25 December 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified October 5, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0341. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 7, 21 October 1776–5 January 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997, pp. 434–438.]

After the battle, the Americans returned to the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware, only to return to defensive positions on the east side of the stream that bordered the east side of Trenton for the victory at the Battle of Assunpink Creek (January 2nd, 1777). From here, Washington took another huge risk and marched in secret overnight towards Princeton.

Scottish Suggestion of the Move on Princeton?

Regarding the overnight march, I note that W.B. Reed (1840: 34–35) suggests (without references) that, ‘Mercer threw out the bold idea that one course had not yet been thought of, and this was to order up the Philadelphia militia, make a night march on Princeton-attack the two British regiments said to be there under Lesley, continue the march to Brunswick, and destroy the magazines at that post. “And where,” was Washington’s question, “can the army take post at Brunswick-my knowledge of the country does not enable me to say?” It was then that General Sinclair gave a full and clear description of the hilly country between Morristown and Brunswick, and the night march as suggested by Mercer was after brief discussion agreed to without dissent’.

Without references, the above cannot be entertained at this stage (if ever), but I would like to investigate this further in future. For the record, Reed’s ‘Sinclair’ must refer to Arthur St. Clair, another Scot who, according to this webpage, studied medicine in Scotland (Edinburgh, as Drs. Benjamin Rush and Jonathan Potts) and, like Mercer, served under Amherst in 1758 during the French and Indian War. Citing David Hackett Fischer, Wikipedia states that ‘Many biographers credit St. Clair with the strategy that led to Washington’s capture of Princeton, New Jersey on January 3, 1777′.

In any case, whether Mercer or St. Clair, or Mercer and St. Clair, it seems that there was a strong Scottish element to the move on Princeton. It is frustrating not to be able to say more, but the limitations of internet-only research are clear in this instance.

Dr. Benjamin Rush: Part I

There is an excellent account of the Battle of Princeton by Jack D. Warren (Executive Director of The Society of the Cincinnati), with a focus on Mercer’s role. Importantly, it discusses the report of Dr. Benjamin Rush, discussed below. n.b. I think I became aware of the usefulness of Rush as a source for Mercer, and the need to locate his autobiography, through the above piece, but I’m so tired now that I can’t say for sure, and it may (also) have been via the ‘Writings’ section in Rush’s Wikipedia. In any case, it really is a great read, and a reminder that we must #SavePrinceton Battlefield.

In the following extract from his autobiography (see below) available on Archive.org, Rush records meeting both St. Clair and Mercer at Trenton. I think this meeting was on January 1st, 1777, the day before the Battle of Assunpink Creek.

‘While the Philadelphia Militia lay at Crosswicks, I rode to Trenton to spend the day with some of the officers of the regular army which still remained there. I alighted at General St. Clair’s quarters. I alighted at General St. Clair’s quarters where I dined and spent the afternoon with General Mercer and Col. Clement Biddle. It was a day which I ever since have remembered with pleasure. Col. Biddle gave me the details of the victory at Trenton a few days before. The two Generals, both Scotchmen, and men of highly cultivated minds, poured forth strains of noble sentiments in their conversation. General Mercer said “he would not be conquered, but that he would cross the mountains and live among the Indians rather than submit to the power of Great Britain in any of the civilized States.”’

Rush was only in earshot of the Battle of Princeton, spending that night with the wounded from Assunpink Creek. The following is his description of c.January 2nd to c.January 4th:

‘In the evening all the wounded, about twenty in number, were brought to this hospital and dressed by Dr. Cochran, myself, and several young surgeons who acted under our direction. We all laid down on some straw in the same room with our wounded patients. I slept two or three hours. About four o’clock Dr. Cochran went up to Trenton to enquire for our army. He returned in haste and said they were not to be found. We now procured waggons, and after putting our patients in them directed that they should follow us to Bordentown, to which place we supposed our army had retreated. At this place we heard a firing, we were ignorant from whence it came, until next morning, when we heard that General Washington had met a part of the British army at Princeton on his way to the high lands of Morris county in New Jersey-through a circuitous route that had been pointed out to him the night before by Col. Jos. Reed, and that he had defeated them.’

The Battle of Princeton (January 3rd, 1777)

The Battle of Princeton – and the entire ‘Trenton-Princeton’ campaign – is featured in the film ‘Winter Patriots‘ on the George Washington’s Mount Vernon website.

For the purposes of this piece, the reader should know that, en route to Princeton, the British under Mawhood – who were heading to the presumed positions of the Americans around Assunpink Creek – spotted the Americans and turned back to attack the American flank. At this point, Mercer was dispatched to counter the British thrust, with the combatants meeting at the site of Clarke’s Farm.

(We note with the earlier caveat that W.B. Reed (1840: 36) writes concerning this action: ‘As the day broke a large body of British troops was discovered apparently in march to Trenton, and after pausing to confer with Washington, who arrived on the field in a short time, the bold design was formed and executed by Mercer, of throwing the brigade between the enemy and their reserve at Princeton, and thus forcing on a general action’).

Despite his reported bravery, Mercer was dismounted and brutally attacked as his troops were routed; a secondary assault against Mawhood by Cadawalader was also in the process of being repulsed when Washington arrived, halting, then reversing the British momentum to the point that the latter fled to the still extant and battle-scarred Nassau Hall before a brief stand gave way to surrender.

The Long Death of Hugh Mercer: Washington’s Letter to Hancock

Back at Clarke’s Farm, and, although gravely injured, Mercer was taken to the nearby (and also still-standing) Thomas Clarke House. As of January 5th, 1777, Washington – writing from Pluckamin, New Jersey, about his success at Princeton – presumed that Mercer had died, as he wrote in a letter to John Hancock:

‘This peice of good fortune is counterballanced by the loss of the brave and worthy Genl Mercer, Cols. Hazlett and Potter, Captn Neal of the Artillery, Captn Fleming who commanded the First Virginia Regiment and four or five other valuable Officers who with about twenty five or thirty privates were slain in the field…’

Reference: “From George Washington to John Hancock, 5 January 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0411. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 7, 21 October 1776–5 January 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1997, pp. 519–530.]

The Long Death of Hugh Mercer: Dr. Jonathan Potts

I have also come across another account purportedly dating to January 5th concerning the aftermath of the Battle of Princeton that mentions Mercer. It is said to have been written by another American who studied medicine in Scotland, namely Dr. Jonathan Potts of the Continental Hospital Department to fellow Revolutionary, Owen Biddle. While I cannot vouch for its veracity, given its placing in a secondary source, my opinion is that it is legitimate, especially as the account of Mercer is more an incidental detail after Potts has described the death of a shared friend:

‘MY D’R FRIEND

‘Tho’ the Acct. I send is a melancholy one (in one respect), yet I have sent an Express to give you the best information I can collect. Our mutual friend Anthony Morris died here in three hours after he received his wounds on Friday Morning […] General Mercer is dangerously ill, indeed. I have scarcely any hopes of him, the Villains have stabbed him in five different places […]

‘It pains me to inform you, that the morning of the action, I was obliged to fly before the Rascals, or fall into their hands, and leave behind the wounded brethren. Would you believe, that the inhuman monsters rob’d the General, as he lay unable to resist on the Bed, even to the taking of his cravat from his neck, insulting him all the time. […]

Your most obedient humble servant, Jon’n Potts

Dated at the Field of Action, near Princeton, Sunday evening, Jan’y 5th, 1777′

Sources: originally seen at Ebooksread.com, then at Archive.org.

This lack of certainty over Mercer’s prospects – and, it should be noted, great respect for him – was also apparent in Baltimore on January 9th:

‘[…] We most earnestly wish you success in your negotiation, and are with perfect esteem, honorable Gentlemen, your most obedient and very humble Servants.

‘Benj Harrison

Richard Henry Lee

in secret Committee

‘P.S. In the engagement near Princeton we lost 15 privates, one Colonel, and Brigadier Gen. Hugh Mercer a very good Officer and a worthy Gentleman.’

Reference: “The Committee of Secret Correspondence to the American Commissioners, 9 January 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified October 5, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-23-02-0082. [Original source:The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 23, October 27, 1776, through April 30, 1777, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1983, pp. 141–143.]

The Committee of Secret Correspondence was, in essence, a foreign office tasked with securing foreign (and British) allies and being the conduit for friendly overseas correspondence, particularly with contacts in France. Richard Henry Lee was not only a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, but was behind the motion that proposed a complete break with Great Britain. Benjamin Harrison V was similarly distinguished, and also signed the Declaration.

The Washington-Joseph Reed Letter

Mercer remained alive, and would linger in the Thomas Clarke House until January 12th, 1777. As the letter I discovered in W.B. Reed’s Oration demonstrated, however, Washington must have been informed that Mercer had survived:

‘When you see Genl Mercer be so good as to present my best wishes to him-& congratulations (if the state of his health will admit of it) on his recovery from death. You may assure him, that nothing but the confident assertion to me that he was either dead-or within minutes of dying, and that he was put into as good a place as I could remove him to, prevented my seeing him after the Action, & pursuit at Princeton.’

Reference: “From George Washington to Joseph Reed, 15 January 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0082. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 8, 6 January 1777 – 27 March 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 76–77.]

Washington’s remark about Mercer’s recovery from death was, of course, delivered in relieved jest for a man he had known (or known of) since at least September 9th, 1758.

Dr. Benjamin Rush: Part II

In his autobiography, Rush writes about travelling towards Princeton after the battle, seemingly on January 4th:

‘We set off immediately for Princeton, and near the town passed over the field of battle, still red in many places with human blood. We found a number of wounded officers and soldiers belonging to both armies. Among the former was General Mercer, an American, and a Captain McPherson, a British officer. They were under the care of a British surgeon’s mate, who committed them both to me. General Mercer had been wounded by a bayonet in his belly in several places, but he received a stroke with the butt of a musket on the side of the head, which put an end to his life a week after the battle.’

As Jack D. Warren summarized: ‘In retrospect, Rush attributed the general’s death to head trauma’.

Funeral Service at the City Tavern in Philadelphia

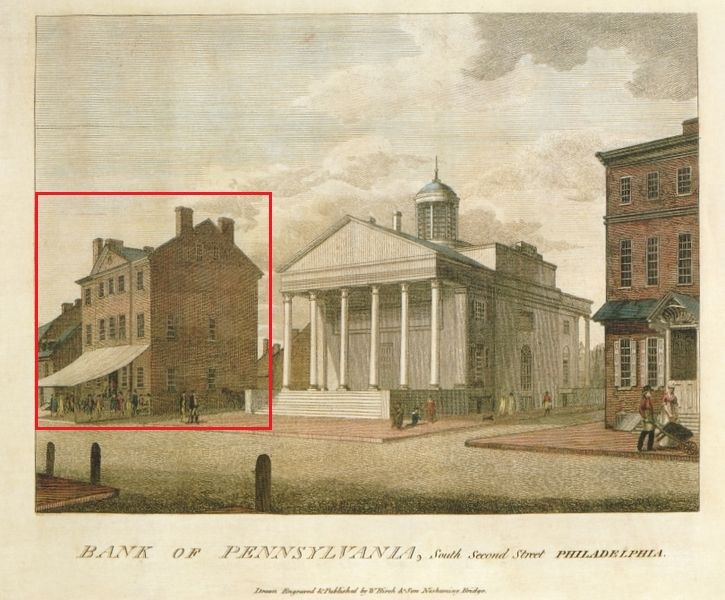

The original City Tavern in Philadelphia:

I do not know how or when Washington discovered the truth about Mercer, but we do know from Christopher Marshall (see below) that the corpse arrived in Philadelphia on the day (January 15th) that Washington wrote the above letter.

There is a tradition that, as Michael Harris puts it, Mercer’s body ‘laid in state’ in the City Tavern (Harris 2014: 53), presumably from the 15th to the 16th. Thanks to Google Books, JSTOR, and the History Society of Pennsylvania‘s ‘The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography‘, I have been able to find the diary of Sarah Logan Fisher (d.1796) – ‘A Diary of Trifling Occurrences’ – that allows us to read a report of Mercer’s funeral:

‘January 16th, 1777: This morning snowed. […] In the afternoon, General Mercer was buried from the City Tavern with all the honors of war. His coffin was covered with a pall, carried by some officers; the drums were covered with black & the music played a solemn dirge. A servant led his horse immediately after the corpse, with the general’s saddle, boots & spurs on; 8 parsons attended, with all the Virginia Light Horse, officers and soldiers. He was wounded in two places at the battle at Princeton, but a violent contusion on his head, it is said, occasioned his death. His loss is thought to be very considerable to the American army, as it is supposed he understood the arts of war superior to any officer in the service except General Washington’.

Reference: Wainwright, Nicholas B., and Sarah Logan Fisher. “‘A Diary of Trifling Occurrences’: Philadelphia, 1776-1778.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 82, no. 4, 1958, pp. 411–465. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20089127.

Burial at Christ Church

Fisher’s fellow diarist, Christopher Marshall, wrote (pgs. 127-8) on January 16th that:

‘This afternoon, was buried from the City Tavern, Gen. Mercer (who died in Princeton from wounds received there the third instant) with all the honours of war, on the south side of Christ Church yard, his body having been brought to town the Fifthteenth instant for that purpose’.

John Armstrong, Jr. (by John Armstrong, Sr.)

There is a final scene relating to Mercer’s death that we can obtain from contemporary correspondence, and it is of John Armstrong, Jr., Mercer’s aide-de-camp being (rather unfairly) chastised by his father in a letter to George Washington for being in a state of disarray after the events of Princeton and its aftermath:

‘The Younger I shall take again with me to Camp-He was faulty in leaving it without waiting on you but the loss of his Patron and Cloaths forced him off for repairs intending not to come farther than where General Mercer lay…’.

Reference: “To George Washington from Brigadier General John Armstrong, 22 February 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified October 5, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0438. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 8, 6 January 1777 – 27 March 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 405–408.]

Commemoration, Both Rapid and Delayed

Although Mercer’s monument was not erected until 1906, the decision to do so at some future point was made rather sooner. The following is an extract from Hancock’s letter of April 9th, 1777, to Washington detailing this:

‘It is with particular Pleasure I transmit the Resolution of Congress directing Monuments to be erected to the Memory of Major General Warren, and Brigadier General Mercer. Every Mark of Distinction shewn to those illustrious Men who offer uo their Lives for the Liberty and Happiness of Mankind, reflects the highest Honour upon those who pay the Tribute, and by holding up to others the Prospects of Fame and Immortality, will animate them to tread in the same Path.’

Reference: “To George Washington from John Hancock, 9 April 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0100. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 9, 28 March 1777 – 10 June 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 98–99.]

On May 2nd, 1777, Nathanael Greene wrote on the subject of Mercer’s commemoration to John Adams:

‘[…] The Monuments you are erecting to the Memory of the great Heroes Montgomery, Warren and Mercer, will be a pleaseing circumstance to the Army in general and at the same time a piece of Justice due to the bravery of the unfortunate Generals. […]’

Reference: “To John Adams from Nathanael Greene, 2 May 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified October 5, 2016, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-05-02-0103. [Original source:The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 5,August 1776 – March 1778, ed. Robert J. Taylor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 171–173.]

Thanks

My warmest thanks to the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia, and to all the readers.

Dr. Tom Horne