Details from ‘LEAD WEIGHTS:

The David Rogers Collection’

– Biggs & Withers, p. 20

It’s all got very meta…

Viking Bullion Weights

I was delighted recently when Gary Johnson told me about a very special Viking bullion weight.

Such weights were, almost certainly, designed to sit in the small balance pans of portable scales to weigh the hacksilver and the other fragmented precious metals (including gold and copper alloy) used as cash within Viking-Age Scandinavian metal-weight (bullion) economies.

An example of one type of bullion weight, the cubo-octahedral, is shown below (we’ll return to these soon), alongside a piece of hacksilver ingot, found in Cowie and Dunblane in central Scotland.

A modern replica of a Viking-Age balance can be seen in the background of the above image; such reconstructions are based on finds we have from the Viking world, including Scotland. Indeed, the following image is of the scale pans and range of bullion weights from the Kiloran Bay boat burial on the island of Colonsay. Deposited in the last quarter of the 9th century, it is now on display in the National Museum of Scotland.

Cubo-Octahedral Bullion Weights

As seen in the Cowie example, cubo-octahedral weights look a little like the multi-sided dice we know from Dungeons and Dragons.

They are of a type of Viking weight known as ‘standardized weights,’ so named because they were seemingly regulated to a (very) approximate weight standard, something we do not want to get into here!

To paraphrase page 33 of my book, A Viking Market Kingdom, standardized weights appeared in cubo-octahedral form from c. AD 860+ and in oblate-spheroid or barrel-shaped form from c. 870+, being popular in those parts of eastern Europe and Scandinavia with large concentrations of dirhams, a silver coin of high silver content that was brought into the Viking world in enormous numbers, feeding and encouraging the silver-dominated bullion economies that took a firm hold from the 9th century.

Weight²

Detail from ‘LEAD WEIGHTS:

The David Rogers Collection’

– Biggs & Withers, p. 20

These weights, and, presumably, most weights were used in and of themselves and in combination with others. What we might not have expected, however, was the existence of a cubo-octahedral weight within a larger lead weight.

As Biggs and Withers (2000: 20) wrote about this wonderful example from the ‘north bank of the Humber’:

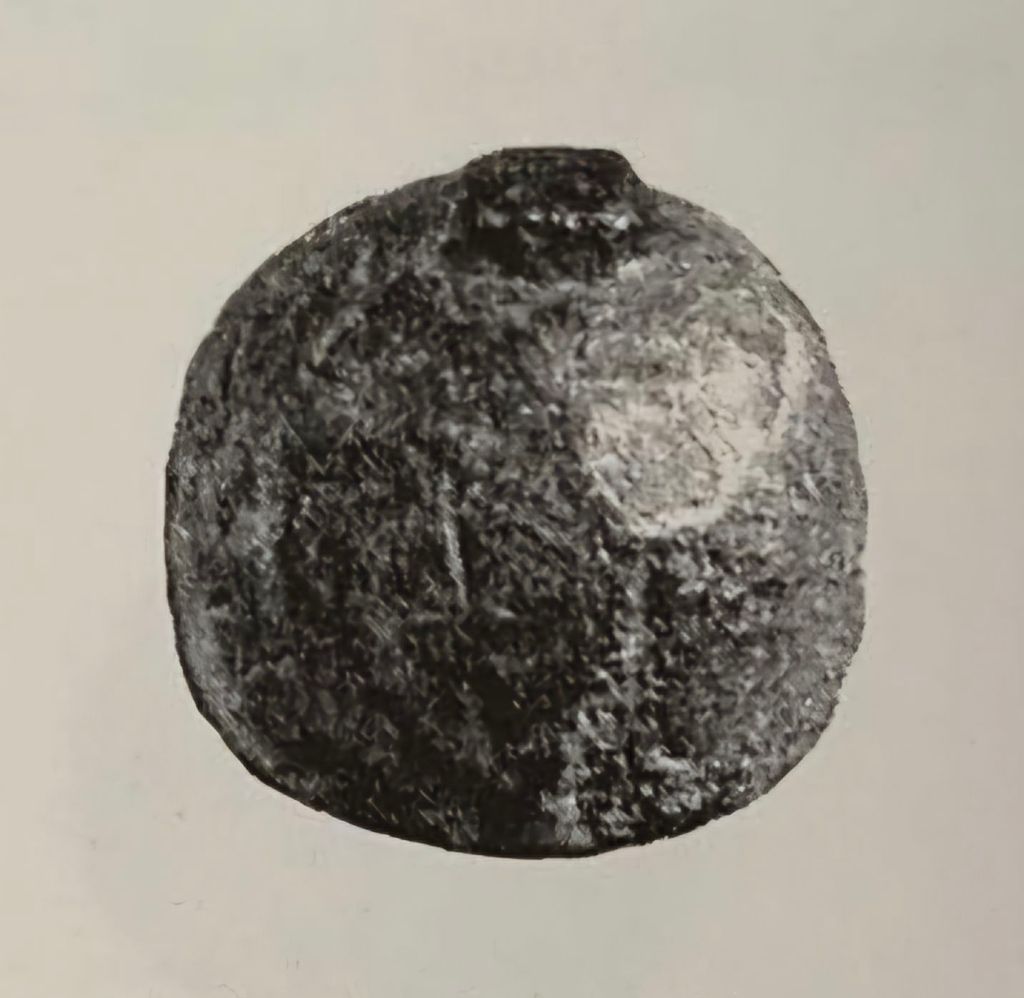

Dome with polyhedral weight

Hemispherical block, with an embedded object showing a square marked with four incuse dots. The identity of the embedded object only became apparent after several examinations. It is a small copper-alloy weight, frequently found in Viking contexts (EW, p.15).

The shape is a cube-with-the-corners-cut-off. Examples with the number of dots ranging from 1 to 6 are known, and the choice of a 4-dot weight for this piece strongly suggests that it was intended to represent half a mark (= 4 ora) on the Viking standard.102g, 27mm, height 22mm

F: North bank of the River Humber

Isn’t this very odd? Well, yes and no.

Yes, because I haven’t seen a weight being part of a bigger weight before, and no because the type of weight that resulted is a type in its own right, namely the lead-inset bullion weight.

Lead-inset Weights

The lead-inset type seems to have been developed in the third quarter of the 9th century by those Vikings we know from a longphort like Woodstown or a Great Army camp like Torksey or Repton.

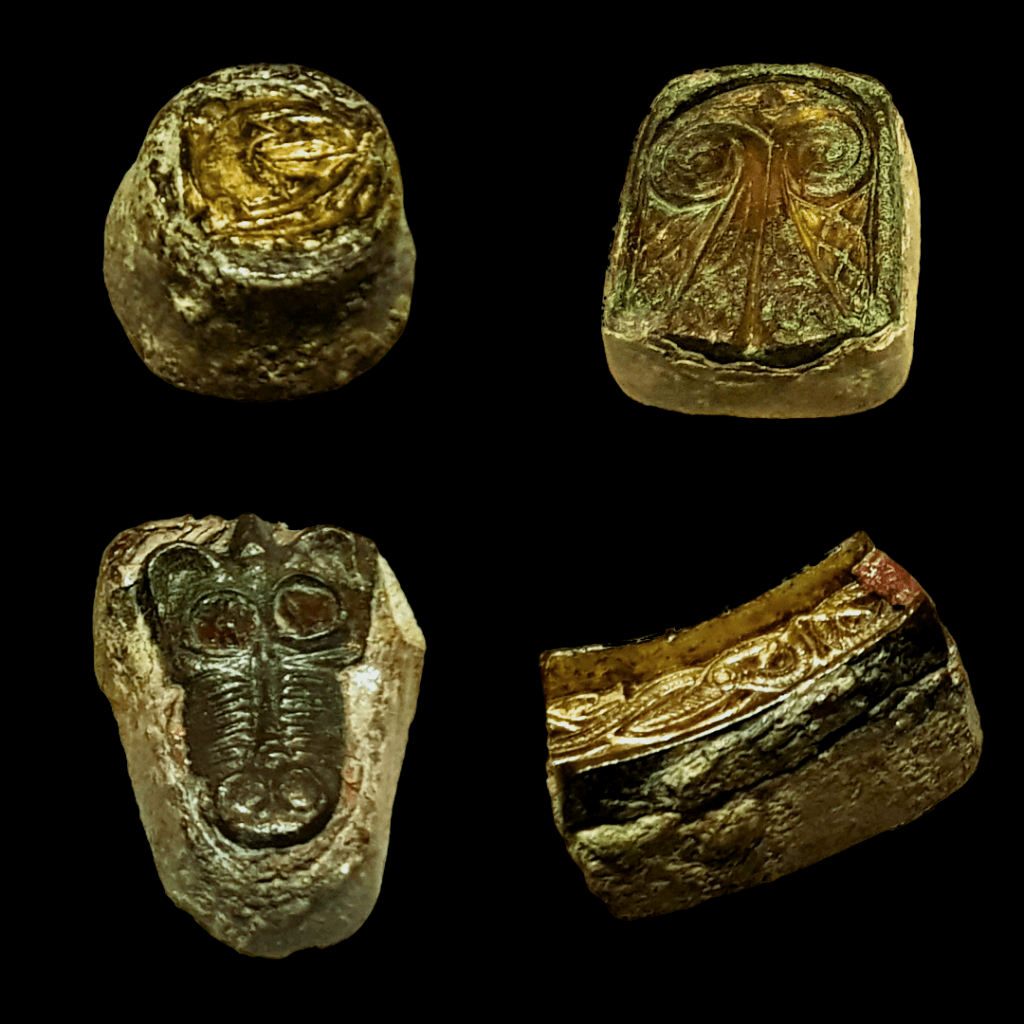

Generally speaking, they seem to be designed for use in bullion transactions and of a bimetallic construction, with a copper-alloy top on a lead base. The copper-alloy element was often a piece of hacked metalwork and also often gilded, with the speculation that it might represent raided metalwork such as gilt brooches, strap-ends and ecclesiastical mounts from Gospel books and the like.

See below for examples from Kiloran Bay:

https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/collections/view/1006250/fullrecord.cfm?id=1570

The North-Humber-ian Weight

Detail from ‘LEAD WEIGHTS:

The David Rogers Collection’

– Biggs & Withers, p. 20

Detail from ‘LEAD WEIGHTS:

The David Rogers Collection’

– Biggs & Withers, p. 20

Why, then, did what we presume was a Viking, or someone working within a Viking bullion economy, doing when they made this equally wondrous and intriguing weight?

‘Iconicity’

I think one answer may be in the fact that we think Vikings saw a powerful and useful visual message within cubo-octahedral weights, possibly because they were associated with the aforementioned transformative influx of dirham silver into Scandinavia. The evidence for this is in the use of cubo-octahedrals within the design of bullion balances and even in personal adornment like arm-rings.

As I wrote in A Viking Market Kingdom pg. 201:

[Standardized weights’] associations with dirhams, in addition to form, material, and distinctive decoration ‘must have been perceived as exact and reliable’, facilitating trust during socially unstable transactions (Gustin 2004a: 265). From this, the extension of cubo-octahedral design to balances, where they sat across from dirhams or other trusted bullion, as well as to personal accoutrements presumed worn by long-distance traders, suggests a desire to display membership of a group that understood commercial rules in a largely gift-giving world. Does it follow, then, that where we find examples of this ornament we also find the network? Here, I look at what Gustin (2004a: 261) described as ‘iconicity’ to explain the thinking behind the transfer of design elements across the scale pan: ‘if there is iconicity between the cubo-octahedral weights and certain cubo-octahedral ornaments, the primary meaning contained in these ornaments […] must have carried the same associations and connotations as the weights’.

In this way, using a cubo-octahedral weight as the inset for the North Bank of the Humber weight might have been to embue the weight with a trust-reinforcing mechanism of the type vital within the potentially fraught world of commercial transactions outside of one’s group.

It Was To Hand and Looked Nice

Alternatively, of course, the cubo-octahedral element may just have been a handy bit of the copper-alloy that tended to top the lead base in lead-inset weight. In any case, it’s more likely than not that we’ll never know, but therein lies the entwined pain and joy of archaeology!

As a so-far isolated example, it’s impossible to say much more than the above, but it’s a great weight to study, and one that’s really making me think more about both cubo-octahedrals and lead-insets, as well as Ingrid Gustin’s brilliant thoughts about iconicity!

Update: A Second Weight²

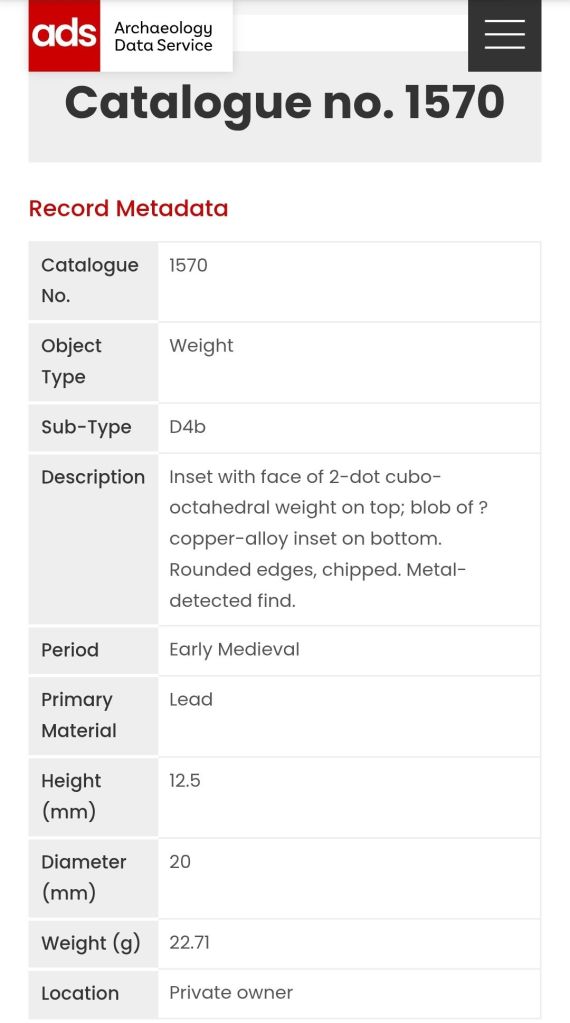

Thanks to Trix Randerson for telling me about a second of these cubo-octahedral lead-inset weights, this time from the Great Army camp known as A Riverine Site Near York / Aldwark, which you can read about in the ARSNY publication, edited by Gareth Williams (2020: 23) and in the Archaeology Data Service online catalogue (No. 1570).

As Trix asks, ‘I wonder if they’re both connected to the Micel Here?’ A great question, to which my response would be that I think they must be!

As seen below, Trix has noted a second example of this type at Aldwark, so I would say we have a new type of Viking bullion weight, one that combines eastern and western (Great Army) metrology and is, thus, a true network weight.

The Cubo-Inset Type

And there we have it: we can now speak of a new type of Viking bullion weight, the cubo-inset, which which is quite the result.

Here, I also thank Colleen Batey for contacting me about this blog to talk about what this weight (type) says about the adoption of weight systems; it certainly opens up a new vista on how Insular Scandinavians were adopting and adapting metrological developments in the long-distance dirham-led trade network to their own tastes.

Ends

Thank you to Gary Johnson for making me aware of this weight.

References:

Biggs, Norman & Withers, Paul (2000) LEAD WEIGHTS: The David Rogers Collection (White House)

Gustin, Ingrid (2004) Mellan gåva och marknad. Handel, tillit och materiell kultur under vikingatid. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International

Williams, Gareth (ed.) (2000) A Riverine Site Near York. London: The British Museum

Leave a comment