You might visit Perth Museum to see the spectacular display of Pictish carved stones, like the extraordinary St Madoes I pictured below, but there is another early medieval star show to which I’d like to draw your attention.

Viking Hacksilver in Central Scotland

You may also have read in a previous blog on here about the hacksilver ingot from Dunblane, currently on display in Dunblane Museum alongside a Viking cubo-octahedral bullion weight, as seen below.

That piece, as this, forms part of a wider research project on the Viking Great Army in northern Britain and its influence, direct or otherwise, on silver economies and trade in what is now northern England and southern and central Scotland.

Balmacolly Bullion

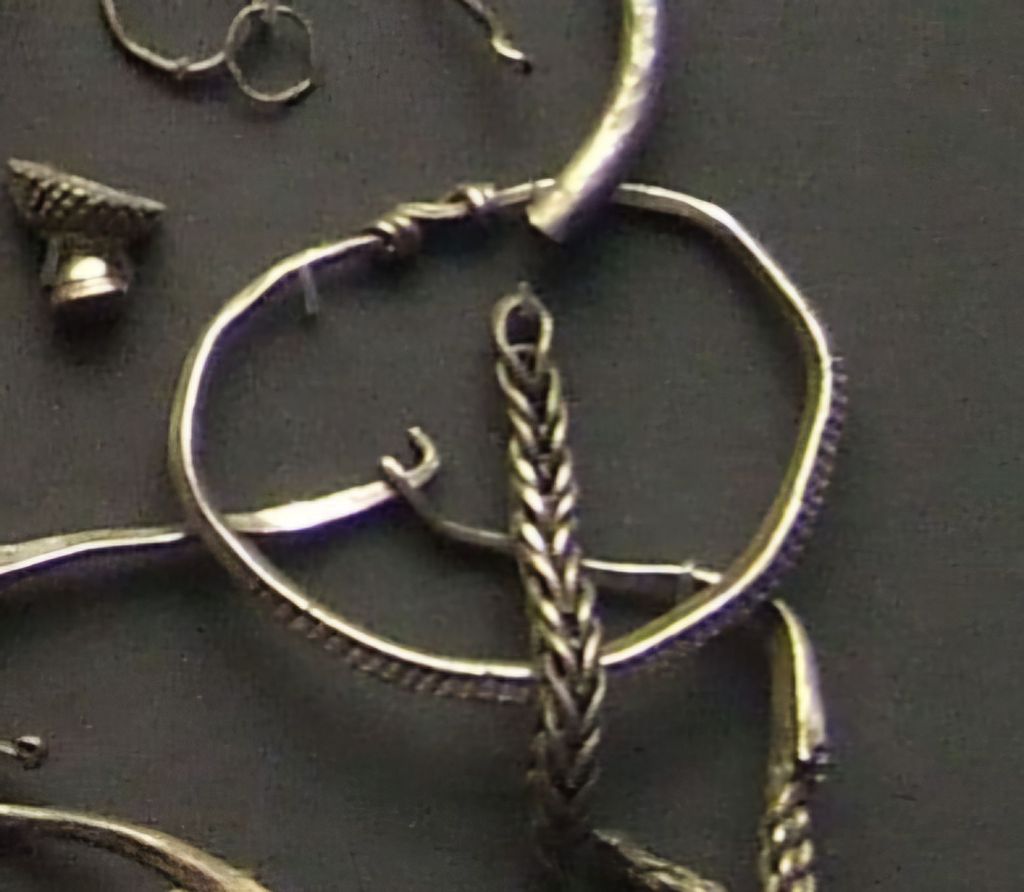

This pair of finds is listed under ‘Fragment of Viking Bracelet or Arm-Ring and a Disc’ found at Balmacolly in Bankfoot, Perth and Kinross. Originally reported to the Treasure Trove in Scotland, and listed as ‘2 fragments of Viking silver,’ they were then allocated to Perth Museum.

These finds represent what we may be confident in thinking of as silver bullion valued for their weight and purity in a Viking, or Viking-influenced, metal-weight economy of the sort gaining some level of traction in southern and central Scotland in the last quarter of the 9th century due to the machinations of the section of the Great Army that campaigned in northern Britain in the 870s under leaders like Hálfdan.

While the disc is largely undiagnostic to the naked eye (although see the work of Kershaw et al. on early medieval silver characterization studies for future possibilities), the hacked fragment of a lozenge-shaped armring will be relatively familiar to those with an interest in the Viking (Age) silver hoards of northern Britain in the period c. AD 870-910+.

While I’ve just started the process of finding parallels for this example, and I’ll aim to update this section as and when, preliminary investigation suggests reasonably strong parallels with coin-dated silver hoards from the 870s to the 910s.

Hoard Parallels

From an initial inspection behind cabinet glass, I would characterize the armring fragment as possibly belonging to a group of annular examples of lozenge- or rhombus-shaped silver rod arm-rings with stamped decoration on their two outer faces.

While we can never know if this fragment is from an annular or penannular ring, similarly stamped lozenge-shaped examples from hoards appear to be the former.

At this point, I should state that I had originally thought that this might be a fragment of Hiberno-Scandinavian or Southern Scandinavian ‘ring-money,’ due to the stamped decoration on a fragment with a similar profile to a type of penannular armring originating in those regions before developing in a plain (unstamped) form in Scandinavian Scotland from the mid 10th century.

However, on reflection, it’s too early in the process of finding parallels to say anything definitely, and, as someone who is by no means an expert in Viking-Age armrings, I would want to run any thoughts I have on this past the likes of John Sheehan and James Graham-Campbell!

Watlington, Huxley and Cuerdale

In any case, a day or two of preliminary research has produced some potentially interesting results in what is very much a work in progress that I’m sharing to see if these thoughts have any merit.

A similar (if complete) example can, I think, be seen in the Watlington Hoard (deposited c. 879-880) from Oxfordshire.

A closer view demonstrates the parallels in section and decoration:

Similarly, the Huxley Hoard (dep. c. 900-910) from Cheshire has a penannular example that parallels the Balmacolly fragment.

Finally, for now, the Cuerdale Hoard (dep. c. 905-910) from Lancashire has more than one potential parallels.

Zooming in on the above image, we can see two possibilities:

While I’m certain many more, and even closer parallels will come to light, my initial hypothesis is that the Balmacolly, Bankfoot armring fragment was most likely deposited between the mid 870s and early 10th century, with the historically-attested 870s activities of the (northern) Great Army in central Scotland favouring a deposition at that time, or relatively soon after.

That it has been reduced to hacksilver, and was found with another piece of probable bullion in the shape of the disc, is further grist to the mill of our work into finding the economic ramifications of the Great Army’s involvement in southern and central Scotland in the 870s.

Thanks to Adrián Maldonado for discussing the arm-ring.

Leave a comment