The Torksey Database

Thanks to the recent Archaeology Data Service release of a visual database for Torksey¹, site of the Viking Great Army overwintering camp of AD 872-73, I’ve been looking again at the plethora of weights designed for use in Viking bullion economies.

Currently, I’m researching the Great Army’s influence in what is now Scotland, so I’m particularly interested in finding parallels between datasets such as Torksey’s and finds in this region.

Before we look at an example of this, it’s best to take a brief step back and explain why the Great Army camped at Torksey and why they were using bullion and its associated weights and scales.

Vikings at Torksey

Torksey was situated on a virtual island at a marshy, but vitally important, nodal junction in Lincolnshire’s Viking-Age communications network, where a major river (Trent) and Roman road (Till Bridge Lane²) met, and near a Roman canal (Foss Dyke).

Due to its strategic and spacious elevated location, Torksey was an idea site for the Great Army, a force that seemingly numbered several thousands and which required a defensible campsite that still allowed for rapid redeployment and control of the key regional transport corridors.

Viking Bullion Economies

A bullion, or metal-weight, economy was one in which metals were used as currency, with their value determined by tests on their weight and purity. Within Viking-dominated payment spheres, the most common metal was silver, but gold and – probably – copper alloys (like bronze) were also used for higher- and lower-value transactions.

Given the need for multiple ‘denominations’ within these economies, these metals were regularly reduced in size to make a certain value of payment, with silver items being cut or hacked into what we know as ‘hacksilver,’ which was the most ubiquitous form of Viking cash.

Weighing it Up

With the phenomenon of increasingly small pieces of hacksilver as Viking bullion economies matured and saw increasing numbers of daily transactions for quotidian goods and services, came the requirement for specialised weights that could weigh the small differences between this form of cash.

From the third quarter of the 9th century AD, a variety of such bullion weights were introduced within Scandinavia. These included the dice-like solid copper-alloy cubo-octahedral type (from the 860s) and the bimetallic, barrel-shaped oblate-spheroid type brought in from the 870s, both apparently the result of the massive influx of silver bullion derived from trade into the Baltic and Southern Scandinavia in the form of (dirham) coins from Central and Western Asia.

Viking Lead Bullion Weights

At approximately the same time that the cubo-octahedrals and oblate-spheroids were being introduced to the Viking world via Southern Scandinavia and the Baltic, Vikings in Ireland and Britain seem to have started making what are known as ‘lead-inset’ bullion weights, being lead bases with a decorative element as a cap. Most commonly, these caps were made of a fragment of hacked copper-alloy (often gilded), but glass and other materials were also used.

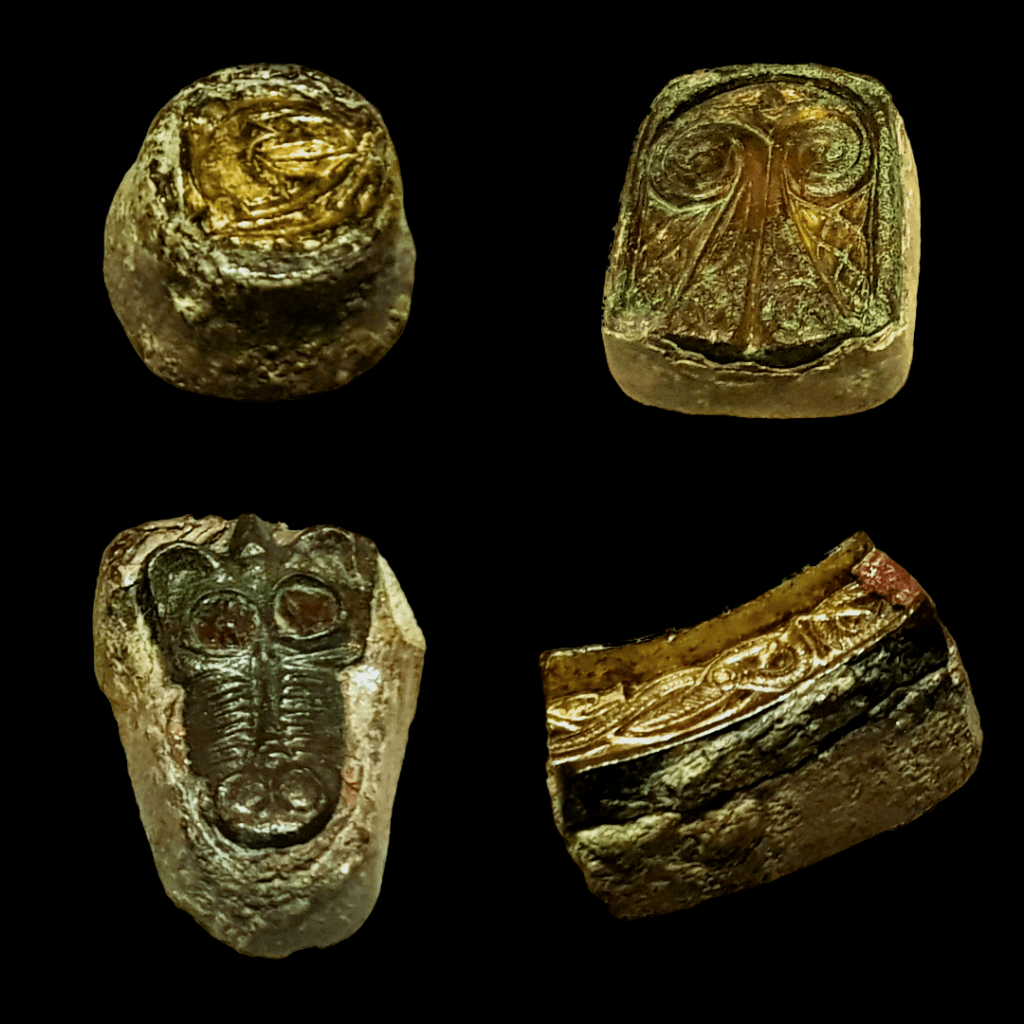

The following example is one of the ‘classic’ types of gilt copper-alloy lead-inset weights, and we can all now study it, thanks to the ADS Torksey Database. While you look at it, magine this weight, alongside other similar examples, in one side of a set of copper-alloy balance scales, with hacksilver cash on the other.

A Viking Great Army Veteran in Scotland?

With that in mind, we can now turn to the late 9th-century Viking boat burial at Kiloran Bay in the island of Colonsay in the Scottish Inner Hebrides and its remarkable collection of bullion weights and set of balance scales.

Looking more closely, we can see six lead-inset weights, four of which have copper-alloy caps:

One of these in particular provides a close parallel to one from Torksey, as seen below:

Kings of the ‘Castles’?

To add to this, another of the Kiloran Bay weights is paralleled at Torksey via this castle-like solid lead weight:

This type is paralleled with several at Torksey, with the latter producing types (with three to five top projections), like the following:

Conclusions

What, then, can we make of the above? I’m not the first to look at links between Kiloran Bay and the Great Army (see Hadley and Richards 2018, with Graham-Campbell’s note), but I would make a strong argument that the late C9th Kiloran Bay individual either had been part of the Great Army, or that they or their burial party wanted to display the fact that they operated within a (northern) Great Army economic and political sphere that included western, southern and central Scotland for parts of the last quarter of the 9th century.

¹ https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/collections/view/1006249/metadata.cfm

² Hadley & Richards, with Haldenby, Perry, Randerson 2024: 65, Life in the Viking Great Army: Raiders, Traders, and Settlers

Leave a comment