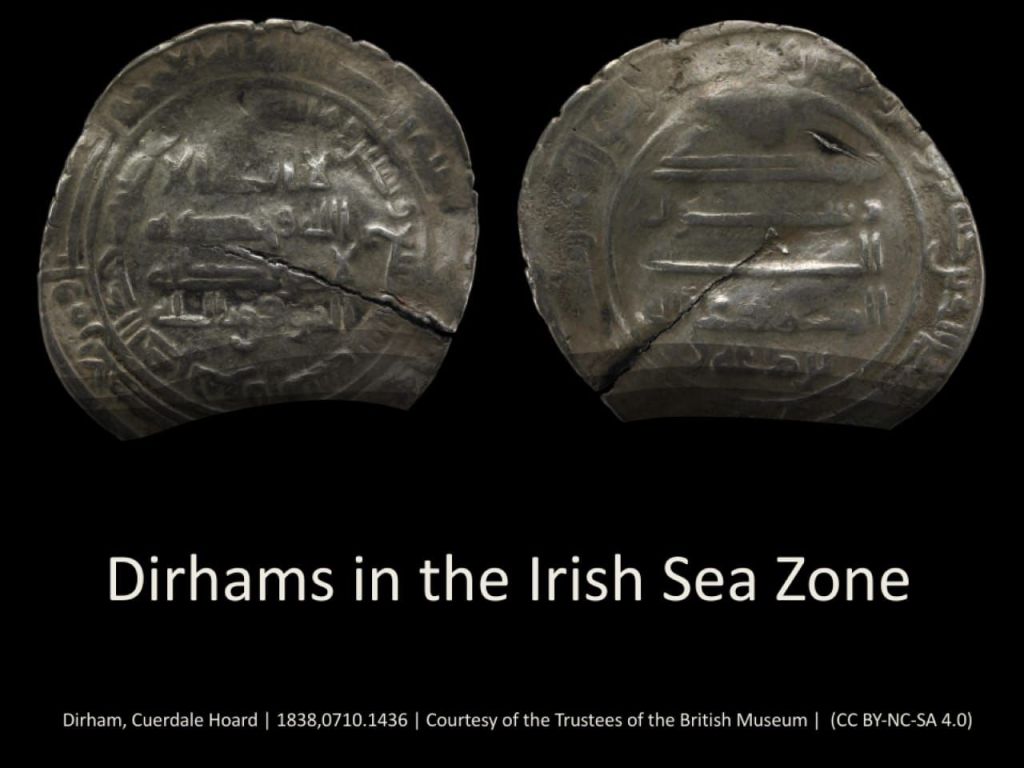

In this paper, I’ll focus on the movement of dirhams into Britain and Ireland, discussing the particular – network – mechanisms I suggest govern their distribution.

I’ll talk about entry and circulation of dirhams in Britain and Ireland (Insular Scandinavia) and the Irish Sea Zone, assessing the role of market sites, polities and individuals in their use and distribution.

Network Kingdom

Ultimately, I suggest looking to the Baltic Sea Zone provides useful models: for example, I suggest a network-kingdom of the type modelled by Blomkvist for a Jorvik-Dublin polity controlled by Ivarr and his Ui Imair descendants.

These were predicated on control, or rather attraction, of market trade and silver currencies. Inclusive of appreciable volumes of Insular dirhams or not, they were – alongside the independent traders drawn to nodal markets – the key mechanisms behind the monetary and exchange developments in Insular Scandinavia between c. AD 850 and 950.

My idea is that Ivarr – being the leader active in both Ireland and Britain – and his descendants set out – seemingly deliberately – to control a network-kingdom based on practices developed in Southern (i.e., Danish) Scandinavia and the Baltic, with the suggestion that Ivarr and the Great Army leadership may have origins in the then Danish Vestfold region where we find Kaupang.

Note here I call Denmark, Skåne, and southern Norway the ‘Danish Corridor’ in order to reflect their largely Danish 9th-century histories.

I argue that control of Dublin and Jorvik, in combination with the ability to coerce and/or persuade those traders and elites hosting and patronizing temporary trading sites such as beach markets and fairs in between these nodes, was an aim of Ivarr and his associates, having seen the success of nodal market and network-kingdom structures in the Danish Corridor and Scandinavian East.

Silver Sources

The wheels of the trade encouraged within network-kingdoms and their nodal structures were greased by liquidity provided by silver bullion, but to what extent were the dirhams so central to Scandinavian homeland silver supply used within the silver stock of Insular Scandinavia?

North Sea Silver Stock

Here, we acknowledge the findings from Kershaw et al., and particularly the suggestion that there was a ‘common ‘North Sea’ silver stock utilized during the last third of the 9th century. That this was, to quote Jane, seemingly derived from ‘western European coinage, with little or no Islamic input. The majority of the analysed silver items [from Westerkleif II and St Pierre des Fleurs] were likely produced in western Europe, being made predominantly of silver obtained locally’.

Is this, then, also true for the Irish Sea Zone silver stock?

Irish Sea Zone / Region

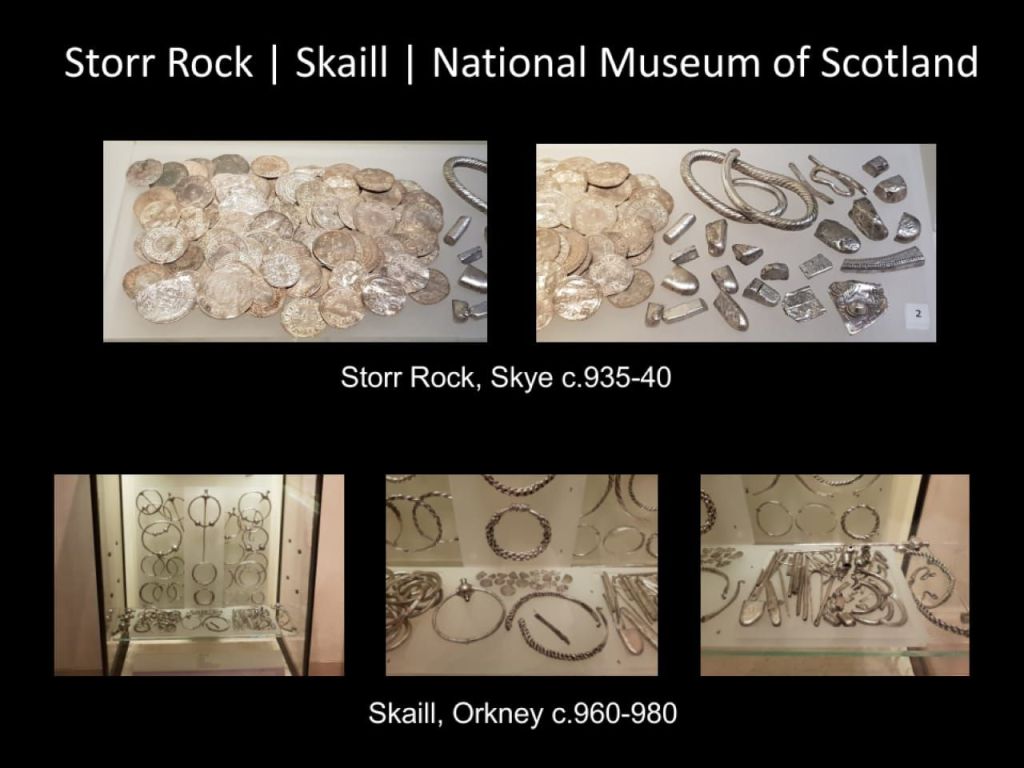

Susan Kruse noticed correlation between dirhams and ingots in Irish Sea hoards, suggesting dirhams were considered part of this circulation, and, thus, part of the non-numismatic silver stock. Moreover, Kruse hinted at a higher dirham element to the silver circulating in the Irish Sea Zone, at least by 935/40 and the deposition of Skye’s Storr Rock dirham-hoard.

Note here: as Etchingham’s Insular Viking Zone and the Orcadian Skaill hoard suggest, the Irish Sea Zone should probably incorporate much of Scandinavian Scotland, including the Northern Isles.

Kruse noted the popularity of ingots as silver stores in the northern Danelaw and Ireland as well as Scotland, seemingly supporting an Ui Imair network-kingdom model for their use and circulation.

Kruse also favoured connections to the Irish Sea providing the source for silver coins found in Scotland, with dirhams providing the silver used in some of the Storr Rock and Skaill ingots.

It seems to me likely it was Hiberno-Scandinavian longphuirt where Kruse’s homogenized silver stock was created. However, any dirham contribution to the stock was likely small, if perhaps a larger proportion than in the North Sea Zone, generally being ‘lost’ within the homogenized stock.

The picture sketched by Kershaw et al. for the North Sea Zone is broadly similar, and we can probably state that both North Sea and Irish Sea zones lacked dirhams in bulk, albeit perhaps being of more importance in the lower volume stock in the latter.

Insular Dirhams

Brown and Naismith’s important 2012 survey acknowledged Insular dirhams ‘may yet have a contribution to make to knowledge of the trade and circulation of silver in the Viking Age’, but they did not look at Insular Scandinavia or the Irish Sea Zone’s position within wider dirham-networks, or use within Insular Scandinavian silver economies.

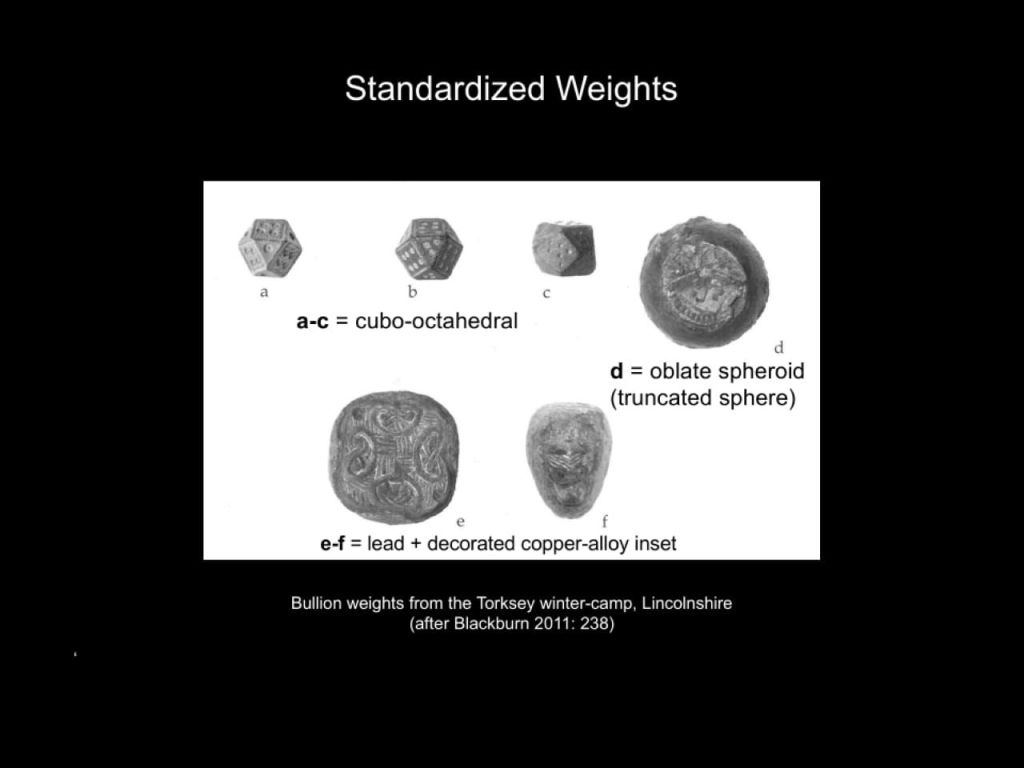

Others have looked at dirhams within silver economies introduced into Insular Scandinavia from the mid-9th century. These include the Viking and Anglo-Saxon Landscape and Economy project and Kershaw, both using PAS data and attempting to link distribution of bullion weights to dirham distribution. Initially, these concentrated only on England and Wales, however, illustrating past regional tendencies in bullion research and the need for holistic studies of silver throughout Insular Scandinavia.

Brown and Naismith’s figure of 350+ can now be updated to 470+ Insular Scandinavian dirham finds. Of these, c.200 are from hoards (43%) and c.270 (57%) from single-finds. I suggest their concentration in England and Ireland was due to the draw of the Uí Ímair nodal markets. I see dirham use or even simply possession as much a marker of Scandinavian market activity within Insular Scandinavia as the Homelands, and one which demonstrated conscious eastern connections.

The 30 dirham hoards in Insular Scandinavia were all deposited in the century after c.870, with 70% dating c.900-930. With at least 69 dirhams between them, the hoards from Cuerdale (31-6) and Goldsborough (35) alone represent c.15% of all Insular Scandinavian examples.

This early 10th-century window was when most dirhams reached Gotland while being imported on a smaller scale into Southern Scandinavia and, to a lesser extent, Norway. This picture of dirhams spreading through the Baltic to Southern Scandinavia and then Insular Scandinavia fits with that of non-numismatic silver from Southern Scandinavia, the Baltic, and eastern Europe.

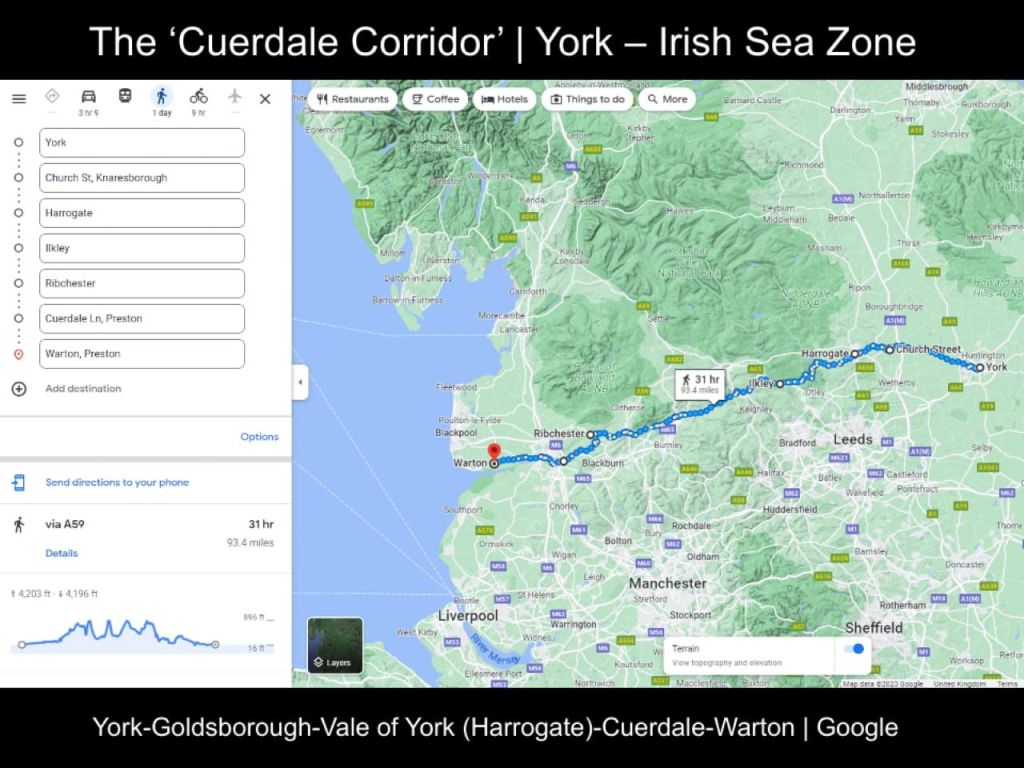

Cuerdale Corridor

Of the Insular hoards, three – Magheralagan (2+ dirhams, c.910, Co. Down); ‘County Derry’ (c.910); and Warton (3, c.925-35, Lancashire) – have an entirely Islamic numismatic element. Magheralagan and Warton were associated with hacksilver, further indicating dirhams were considered bullion. Notably, Warton is 20km due west of Cuerdale, suggesting the Ribble Valley was a routeway for dirham-using Scandinavians. The slide shows the A59 Roman road and Ribble Valley connecting Jorvik via the dirham-hoards of Harrogate (c.927-8), Goldsborough, Cuerdale and Warton, i.e., my ‘Cuerdale Corridor’ connecting Jorvik to the Irish Sea Zone.

Hoard dirhams make up approximately half of the Insular total. Most are deposited around Dublin or directly across the Irish Sea in North-West England and towards York. The latest English dirham-hoard is Furness (dep. 955-7), in a Cumbrian area with a cluster of dirham single-finds.

Blackburn argued connections to eastern dirham-networks ‘persisted […] until the later 920s, while over in North West England it continued somewhat later’. PAS data implies some persevered into the 940s or thereafter and were using newly-imported dirhams. This suggests continuation of northern Anglo-Scandinavian links to Southern Scandinavia, although perhaps via the Irish Sea by then.

The largest concentrations of single or site-find dirhams are at Torksey (124+) and ARSNY / Aldwark (14/15), Great Army winter-camps occupied in the early-to-mid 870s. The overwhelming majority of single-finds are English, with a marked southern and eastern bias compared to hoards. There is one Scottish (Irish Sea Zone) single-find (Stevenston Sands), two from Wales (Llanbedrgoch), two from Man, and a handful in Ireland, including at the Woodstown longphort.

The disconnect between hoard and single-find distributions suggested to Kershaw that the primary area of transactional dirham use was the eastern Danelaw, correlating to concentrations of associated standardized weights. Kershaw argued the predominantly rural scatter differentiates it from Scandinavia, where use tended to cluster in and around urban markets, although this picture is being challenged by subsequent finds from rural northern Norway (See Krokmyrdal for the finds at Sandtorg i Tjeldsund, Troms) and Sweden (See Holm’s work on Jämtland).

The 900-930 period of maximum dirham import into Insular Scandinavia matches the period Samanid dirhams entered Scandinavia, initially and primarily in Gotland. It was 915/20 before Samanid issues begin to predominate on the Scandinavian mainland, so there may be connections between Gotland and eastern Ireland, particularly as Irish Sea Zone examples were minted between 905-914, with some deposited even before appearing at Birka and Kaupang – referencing my work Sheehan noted that:

‘these dirhams seem most likely to have been imported directly into the Irish Sea region from Gotland, presumably to Dublin and through southern Scandinavia, strongly hinting at a formative southern Scandinavian influence behind the establishment of Dublin as a Hiberno-Scandinavian interpretation of Danish-style market sites like Hedeby and Kaupang’.

Sheehan noted Dysart (c.910) contains not only Southern-Scandinavian and Baltic non-numismatic silver, but also Samanid dirhams and a fragment of a Gotlandic type arm-ring, pointing to possible direct links between Ireland and Gotland. Millockstown, Leggagh, and (probably) Drogheda also contain early Samanid dirhams, as do three c.920s Cuerdale Corridor hoards with Hiberno-Scandinavian characteristics (Goldsborough, Bossall/Flaxton, Bangor), further suggesting a Gotland/Southern-Scandinavian link with Dublin. Sheehan (referencing me) uses the fact early Samanid dirhams and hoards around Dublin containing Baltic non-numismatic silver were seemingly deposited around the 902-917 exile to suggest a particular Southern Scandinavian:

‘seized the opportunity of a power vacuum in Dublin to develop a new trade network […] This may not have been without precedent. Were […] links between Dublin and the Southern Scandinavian/Baltic region in the early tenth century a repetition of the 840s, when ambitious ‘Danes’, perhaps operating out of Kaupang, may have exploited disruption among the Dublin Scandinavians to establish a trading site in their own image?’

While near-absence of dirhams from Dublin and Jórvík is noted (although fragments potentially eluded rescue excavations), they remain the most likely conduit or draw.

Gooch’s analysis of post-895 northern Danelaw coin hoards showed a band stretching from Norfolk towards the Cuerdale Corridor, north Wales, Man, and eastern Ireland. Seemingly, their distribution provides the missing link between hoards and single-finds in that they link the northern Danelaw with Dublin and its hinterland. This hints at the economic sphere of influence of Uí Ímair network regents and the traders connected to them. There is also a notable correlation between northern Danelaw issues and dirhams in the Storr Rock (c.935/40, Skye), Skaill (c.960-80, Orkney), and Machrie (c.970-980, Islay) hoards, suggesting additional influence in the maximal Irish Sea Zone.

The Insular Scandinavian period of circulation of dirhams (roughly matching that of importation) is c.871-980, with most deposited c.900-935. Coin-dated deposition dates from Croydon to Skaill. Skaill contains the dirhams with the latest mint dates for Insular Scandinavia, with Samanid dirhams dating to 943 and Abbasids to 945. Based on a standard 10-15 year lag, this suggests entry of the latest Skaill dirhams into the region around the mid-950s, which could fit with the fall of Jórvík out of the Uí Ímair network-kingdom following Eiríkr’s death. This changed the raison d’être of the Uí Imair polity towards a sharpened focus on the Irish Sea Zone.

Dirhams in England

In 2005, Naismith noted ‘the general similarity of the English and Scandinavian find-patterns shows that, at least until c.925, England was part of the network connecting Scandinavia to the caliphate’.

While more difficult to observe the ‘pulses’ of Abbasid minting discernible in large Scandinavian hoards in Insular Scandinavia, traces are apparent where enough dirhams survive, as in Cuerdale. It seems clear, however, that dirham-network bonds between Danelaw and Southern Scandinavia were weak, with the steep decline in coins minted after c.910 not reflected in the Baltic, where decline in imports only occurred from the mid-10th.

The general picture of English dirham distribution has changed little since Naismith’s 2005 paper, which has a strong correlation to the distribution of hoards containing northern Danelaw coins, as per Gooch. English dirham-hoards tend to be a northern phenomenon, whereas single-finds demonstrate more of a bias towards east and south. Hoard distribution reflects my Cuerdale Corridor, and this idea of regular traffic on a Jorvik-Dublin axis complements Williams’ suggestion Cuerdale might just as well have been accumulated at Jórvík as Dublin, with earlier confusion over its provenance demonstrating similarities in silver traffic and use between Uí Ímair regions.

North-West England | Campsites

The relative lack of single-find dirhams in North-West England suggests this was a region through which bullion currency passed rather than was used, although the Cumbria cluster (and hoards) may suggest market use here, perhaps with a beach market in northern Man. For definite active use, however, we turn to the winter-camps.

Torksey’s highly-fragmented chopped dirhams indicate currency use, while relatively whole Anglo-Saxon coin point to use within the local Münzgeldwirtschaft. Moreover, Torksey demonstrates these multi-metallic bullion and coin economies existed together from ‘the very outset of Viking settlement in the west’ (Hadley & Richards).

Importantly for arguments suggesting long-term economic goals from examination of the Great Army’s operational priorities, Torksey suggests sophisticated commercial understanding arrived in Britain at least partially formed before developing its own adaptations, such as lead-inset weights.

ARSNY / Aldwark is also replete with items pertaining to bullion-based networks linking the Great Army with the Irish Sea Zone and Southern Scandinavia, as Williams noted:

‘The presence of [dirhams] and weights common in Scandinavia suggests […] the driving force for this economic model came from southern Scandinavia’.

This echoes Kershaw’s conclusion for rural Yorkshire where: ‘single finds highlight sources of silver and weights in both southern Scandinavia and the Irish Sea region. Settlers and/or visitors from these regions, and their descendants, may have been the principal participants in Yorkshire’s bullion economy’.

ARSNY / Aldwark has produced nearly 300 weights, 70 silver pieces, 106 coins, two hackgold fragments, and a balance fragment. The quantity of ARSNY / Aldwark material from Ireland may suggest Great Army leaders had been operating previously in Irish Sea Zone longphuirt. Intriguingly, the likely Woodstown longphort floruit (early 860s?) coincides well with leaders travelling to England for the campaigns that seemingly produced hoards such as Croydon, the earliest English dirham hoard.

For Kilger, ‘The earliest hacksilver hoards of Western Europe around the Irish Sea and in England, such as Croydon and Cuerdale, or in the Netherlands, may be linked principally with the Danish Vikings’. Croydon (dep. 871/2) also contained a Danish broad-band arm-ring of the type developed in Hiberno-Scandinavian contexts, supporting my idea of Ívarr et al. as the originating mechanism of the Baltic and Southern Scandinavian bullion networks in both Britain and Ireland. It seems likely these warriors provided the link between longphuirt, winter-camps, and Southern Scandinavia.

The window of dirham use in England had appeared small (c.870-930), with dirham-hoards disappearing roughly in line with Aethelstan’s conquest of York in 927. However, Yorkshire’s Cottam dirham dating to c.928/9, and one from Buxton with Lammas (Norfolk, c.927/8), both unlikely to have been deposited before the mid/late-930s, could suggest that Aethelstan’s death in 939 and York’s re-conquest by the Uí Ímair re-opened eastern links until Eiríkr’s death in 954.

While late finds may mean that we no longer must stick to the traditional paradigm that Danelaw dirham imports ceased definitively in 927, it remains clear dirhams circulated in that maximal Irish Sea Zone inclusive of the Northern Isles until Skaill was deposited. This parallels Homeland dirham chronology, suggesting dirhams could enter the Irish Sea region through the Round-Scotland routeway if York was under Anglo-Saxon control.

Kershaw observes it cannot be discounted that Cottam’s dirham, whose condition indicates lengthy circulation, entered Insular Scandinavia via Scottish and Irish Sea routes as late as the 940s and be unrelated to a continuing import of bullion into the northern Danelaw. That said, it remains possible Cottam entered the Danelaw directly, with Kershaw open to the possibility Dublin control of Jórvík after 939 reinvigorated bullion, noting ‘use of bullion east of the Pennines would have helped to facilitate economic interchange between the two Viking centres’.

Dirhams in the Irish Sea

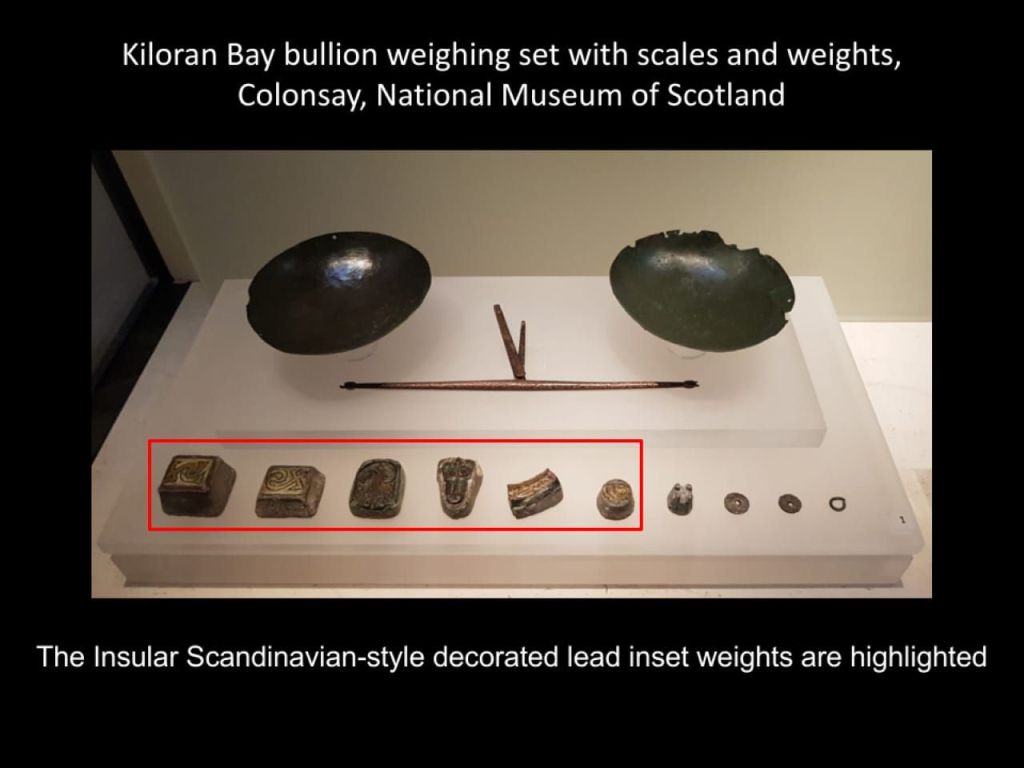

Dirhams are overwhelmingly found in hoards in the Irish Sea Zone, with only a handful of single-finds. Although rare, the discovery of two fragments at Llanbedrgoch on Anglesey, two from Man (one possibly from a beach market), one from the Ayrshire coast, and several from Cumbria suggests use as payment. Furthermore, the Ayrshire find at Ardeer links with bullion weighing equipment found in the Western Isles at Kiloran Bay on Colonsay and nearby Gigha.

Naismith noted ‘extensive connections between […] York and Dublin’ apparent in the regular presence of coins from Jórvík and the southern Danelaw in Irish hoards. Similarly, Hiberno-Scandinavian silver bullion in the Cuerdale Corridor dirham-hoards at Cuerdale and Goldsborough suggests the bi-directionality of these connections. The probability – based on the Danelaw hoard distribution on a Dublin-Jórvík axis – points to a preferred Cuerdale Corridor routeway that extended to the Wirral and thence Bangor and Anglesey in north Wales.

Dirhams in Wales and Ireland

It is notable that the only Welsh dirham-hoard links to both Ireland and the Danelaw: five dirhams were found in the 1894 Bangor ‘A’ hoard (c.927, Gwynedd), part of a typical Insular Scandinavian hoard containing, like Dunmore Cave (no. 1) (928-30, Co. Kilkenny), a mixture of Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Scandinavian, and dirhams alongside hacksilver. This combination is paralleled by Cuerdale, Dysart Island (no. 4), and Leggagh (c.923-924, Co. Meath). With 19 dirhams and distinctive non-numismatic pieces, Sheehan suggests ‘Dysart embodies more completely than any other Irish hoard the contacts that existed between the southern Scandinavian/Baltic region and Viking-Age Ireland’. Moreover, as Blackburn noted, these hoards seemingly reflected ‘money that had in part travelled across the northern Danelaw to the Irish Sea’.

In Ireland itself, dirhams form part of the numismatic element of 77% (10/13) of hoards deposited c.900×930/5, suggesting that dirhams were more likely to pass through north-west England and Wales en route to Hiberno-Scandinavian markets. Indeed, dirhams from the Woodstown longphort and ‘near Dublin’ fit the pattern of dirham association with markets.

Although there is an outlier in the ‘Co. Meath’ hoard deposited c.970, the main period of dirham influx and circulation in Ireland ended, as England, around the time of Athelstan’s capture of York; we think here of the Glasnevin (Co. Dublin), Dunmore Cave (no. 1), and ‘Co. Kildare’ hoards, deposited c.930. The latest securely provenanced Irish single-find dirham – the Volga Bulgar counterfeit dated to c.900-10 (lost c.910-925?) from Carrowreilly in Co. Sligo also fits this pattern.

As Blackburn asked: ‘was the simultaneous demise of dirham in England and Ireland linked, the dirhams having generally come via the Danelaw in the company [of] Anglo-Scandinavian coins, or did Ireland receive some dirhams directly from Scandinavia or via the Scottish settlements?’. Here, Blackburn argued for ‘more direct’ dirham-network links between Scandinavia and Ireland in the early 10th century on the basis that the lost Drogheda (c.905-10) and Co. London/Derry (c.910) hoards apparently contained ‘many’ dirhams.

Dirhams in Scotland

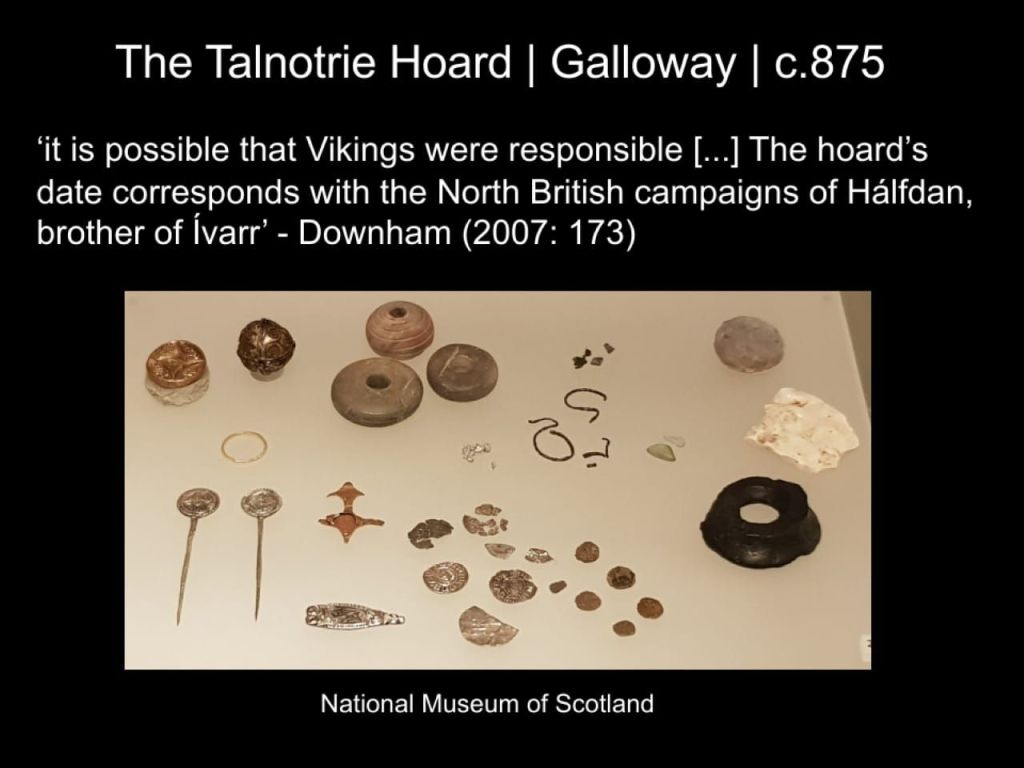

Blackburn argued dirhams ‘continued to arrive in Scotland until the mid-10th century’ on the basis of the Storr Rock and Skaill hoards. While we know too little about the single alleged dirham from the lost Machrie hoard (c.970-80, Islay), we should consider the Talnotrie hoard, with its winter-camp-like combination of decorated lead inset weight, Northumbrian stycas, Anglo-Saxon pennies, and dirhams as relating to c.874-5 Great Army activity and, therefore, the earliest dirhams in the region.

Storr Rock (c.935-40, Skye) included ingots, Hiberno-Scandinavian hacksilver, and ‘Permian’-style spiral-ring fragments. Of coins, there were 19 mostly whole dirhams, 90 Anglo-Saxon, and two Anglo-Scandinavian (from the Lincoln mint of the Uí Ímair king of Dublin and Jórvík, Sihtric Cáech). The latest of the dirhams dates to c.932 and the Anglo-Saxon coins have a 933-938 tpq. Metcalf noted the numismatic element was similar to contemporary Irish examples like Leggagh. Similarly, the presence of Hiberno-Scandinavian and [Baltic] non-numismatic elements alongside Irish ones suggested to Graham-Campbell that Storr Rock was, in all but location, an Irish Sea Zone hoard.

Skaill (deposited c. 960-80) also owed a considerable quantity of its non-numismatic silver to Irish Sea sources, something reflected in finds from the associated contemporary settlement. Whereas the 19 Storr Rock dirhams formed a minority amongst coins from England, however, only two of the 21 Skaill coins were non-Kufic, with one Aethelstan and one Anglo-Scandinavian Jórvík (swordless) ‘St Peter’ issue. In contrast to Storr Rock, most of the 19 Skaill dirhams are highly fragmentary, suggesting a biography more typical of market/longphort/winter-camp use.

Skaill’s latest legible dirhams were minted as late as 945/6. Graham-Campbell and Batey argued it was ‘Probable that the dirhams which reached Scotland did so by way of Denmark and the Danelaw area of England (whether by way of York or through the Irish Sea Region)’, coming to this conclusion via the massive disparity between dirham numbers in Southern Scandinavia and Norway.

While Irish Sea Zone influence on the non-numismatic element suggests Scotland received its dirhams, spiral-rings, etc. via a network passing through the Danelaw and the Irish Sea Zone, it remains possible these eastern elements came from maritime contacts between Scotland and Jórvík. Indeed, Metcalf named Jórvík as the ‘proximate source for the dirhams’ in Storr Rock.

Whether eastern material in Scotland came via Jórvík, via Jórvík and the Irish Sea, or directly across the North Sea has yet to be resolved, but it seems reasonable to suggest all three were utilised.

Multiple Market Model

How, then, might dirhams have been used in the Irish Sea Zone?

I would answer this by saying there may be many more historically-invisible coastal temporary market sites, like the recently-discovered Sandtorg in Troms, where traders could have broken journeys and traded while criss-crossing the Irish Sea Zone, as at the possible beach market on northern Man or the sandy beaches of Ardeer in Ayrshire or Kiloran Bay on Colonsay.

This provides a potential model for how a route segment (of a greater trade network) through a largely non-urbanised Irish Sea region worked. Here, natural harbours and traffic junctions were used as way-stations and temporary markets by nodal-market traders heading ultimately to Dublin, Jorvik, Kaupang or Hedeby, and also found patronage as part of second-tier Braudelian ‘tramping’ trade networks used by potential traders as that buried with an apparent bullion currency weighing set perfect for dirhams at Kiloran Bay.

End.

Listen to this blog as a podcast:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/legalcode.en

Leave a comment