If we think of the Great Army, we tend to think of it in the southern half of Britain. This is, of course, logical, as the vast majority of recorded activity of this force between circa AD 865 and 878 occurs from York southwards.

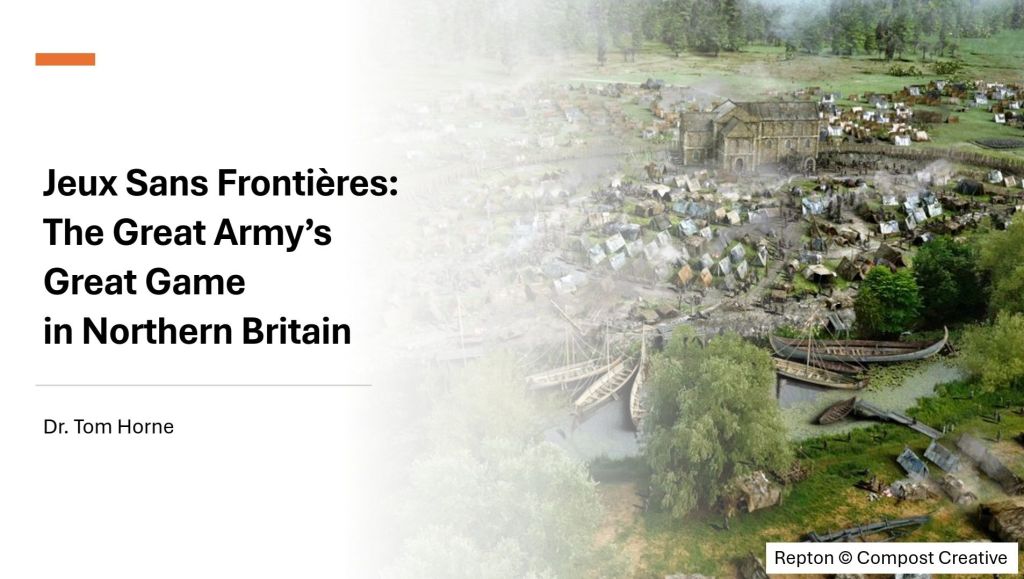

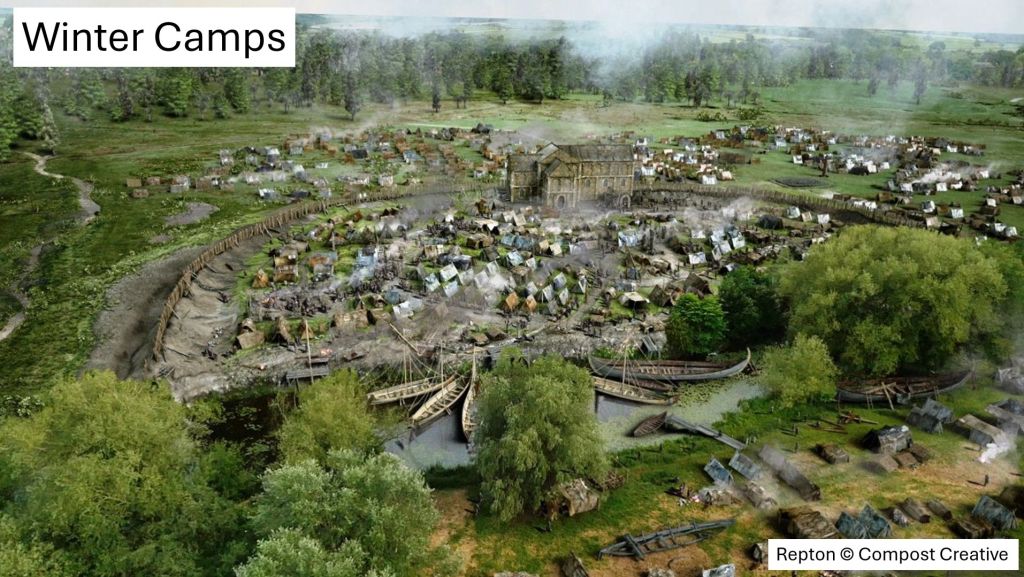

You will probably have heard of the winter camps at Torksey in Lincolnshire and at Repton in Derbyshire (an imagining of which can be seen here), but our increasing ability to identify the telltale ‘signature’ of the Great Army, largely via what Blackburn, Hadley and Richards gleaned from Torskey and responsible metal detectorists, means that new camps associated with the Great Army are coming to light, as per the work of Cat Jarman and Mark Horton at Foremark, located near to, and likely associated with, the well-known camp at Repton uncovered originally by the Biddles, and the work of Kershaw, Jarman, Weber, Horton, and the community archaeology teams led by Jane Harrison et al. at the ‘Near Felton’ site in northern Northumberland.

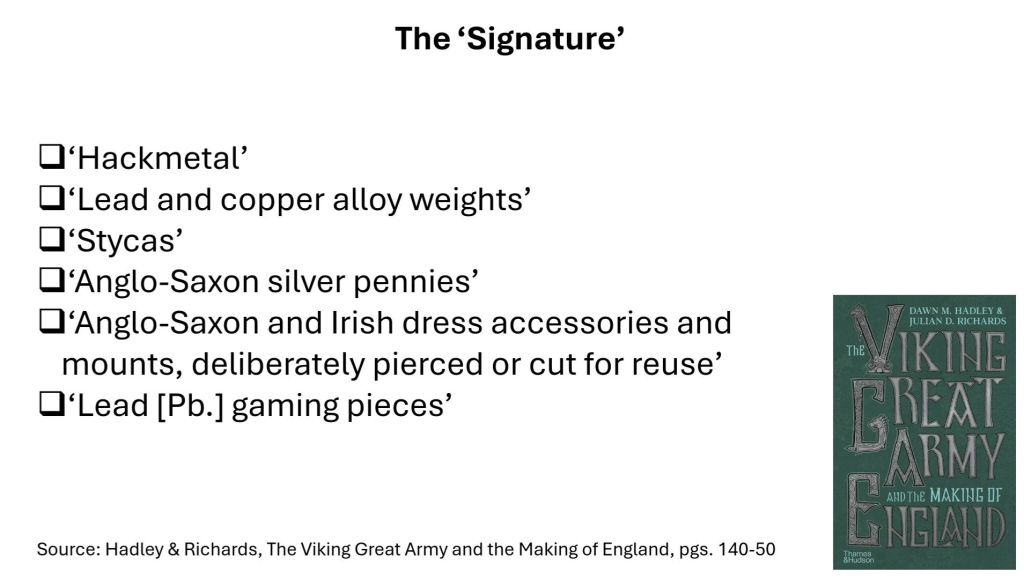

The ‘Signature’

What, then, are the telltale signs of a Great Army camp? In ‘The Viking Great Army,’ Hadley and Richards have honed their signature¹⁰ to include six principal elements, being:

1) ‘Hackmetal’

Hackmetal was generally silver, but could also be other metals like gold and copper alloys, as Kershaw notes. Here, Adrián Maldonado reminded me of Gareth Williams’ suggestion that Vikings were trading lead at Aldwark.

2) ‘Lead and copper alloy weights’

These are commonly referred to as ‘lead inset’ weights, as the inset decorative element of these weights were generally gilt copper alloy offcuts, but some included non-metallic decoration, like the glass examples from Torksey and Dumbarton Rock.

3) ‘Stycas’

Although these low-denomination copper alloy coins produced in 9th-century Northumbria are common in their own region, they are often considered to have been carried by the Great Army when outside Northumbria, as with the 170+ Torksey examples, and those from the Kiloran Bay burial of circa 870-900¹¹ from the Hebridean island of Colonsay.¹²

4) ‘Anglo-Saxon silver pennies’

Again, these can generally be considered signs of the Great Army where found outside their region of origin, as with the Mercian coins from Galloway’s Talnotrie hoard¹³, often demonetised by being chopped or pierced.

5) ‘Anglo-Saxon and Irish dress accessories and mounts, deliberately pierced or cut for reuse’

Typically, these were either considered hackmetal currency and/or were used to decorate lead weights, and commonly included Anglo-Saxon strap-ends.¹⁴

6) ‘Lead gaming pieces’

Used for tafl games, and found at Repton, Foremark, Torksey and Aldwark, as well as the potential ‘Near Felton’ site.¹⁵

Note how the ‘signature’ revolves around the mechanisms of a bullion economy, with hackmetal and foreign coins being used as a form of cash, valued for their weight and quality of the metal and assessed via test marks and with scale balances and lead weights (including lead inset varieties), such as discovered as a set at Kiloran Bay.

Finally, how ‘great’ was this Great Army? While Peter Sawyer argued via historical terminology for the possibility that it was small, archaeological work on the vast Torksey winter-camp in Lincolnshire¹⁶; at Repton and Foremark in Derbyshire; at Aldwark; and at the ‘Near Felton’ possible Great Army site is suggestive of a large force (of several thousands), which one could see as responsible for the huge political changes wrought in their name.

Viking Leadership in Britain and Ireland

I will not go too deeply down the rabbit hole of the Viking protagonists, save this list of the main characters active in northern Britain and Ireland. Note only that I consider the leaders mentioned in the Irish and British sources as being one and the same, from the idea that the Great Army shared its main protagonists of Ívarr, Óláfr, Hálfdan, and Ásl in particular with those based in Ireland and, previously, in Frankia and Frisia.

For more on these individuals, I direct you to ‘Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland’ by Downham and ‘From Pictland to Alba’ by Woolf.

– Ívarr (ON) | Ímar (OI)

– Hálfdan (ON) | Albann (OI)

– Óláfr (ON) | Amlaíb (OI)

– Ásl (ON) | Auisle (OI)

The Coming of the Great Army

We now turn to the arrival, in 865, of the Great ‘heathen’ Army in England, via the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

‘…the same year came a large heathen army into England, and fixed their winter-quarters in East-Anglia, where they were soon horsed; and the inhabitants made peace with them’.¹⁷

According to the Chronicle, the Army then established an overwintering base at Thetford in Norfolk, being the first of the winter-camps. Thereafter, the Chronicle notes for 866 that:

‘This year the army went from the East-Angles over the mouth of the Humber to the Northumbrians, as far as York. And there was much dissension in that nation among themselves; they had deposed their king Osbert, and had admitted Aella, who had no natural claim. Late in the year, however, they returned to their allegiance, and they were now fighting against the common enemy; having collected a vast force, with which they fought the army at York; and breaking open the town, some of them entered in. Then was there an immense slaughter of the Northumbrians, some within and some without; and both the kings were slain on the spot. The survivors made peace with the army’.¹⁸

Having taken York on the 1st of November 866, the Great Army moved to the Tyne, only for the Northumbrian king Osbehrt, now allied with his erstwhile rival Ælla, to retake York for a brief period before the Army returned to retake York and kill Osberht and Ælla on the 21st of March, 867.¹⁹

Here, we can correlate the Chronicle with the Irish ‘Annals of Ulster’, with the latter noting for 867 that: The dark foreigners won a battle over the northern Saxons at York, in which fell Aelle, king of the northern Saxons.²⁰

AD 866-71 in Northern Britain

Until now, Viking activity in mainland Scotland has been seen as almost exclusively as coming from Ireland and not via the Great Army: the Annals of Ulster tell us that, in 866: Amlaíb and Auisle [i.e., Óláfr and Ásl] went with the foreigners of Ireland and Scotland to Fortriu, plundered the entire Pictish country and took away hostages from them.²¹ ²²

An important aside here is that, in 863, Amlaíb (Óláfr), and Auisle (Ásl) and Ímar (Ívarr) were described as ‘three kings of the foreigners’ by the Annals.

After spending what may have been three months of 866 in Pictland²³, Óláfr seems to have returned to Ireland in 867, prompting Downham to ask ‘why Óláfr left North Britain at a time when his campaigns there were going so well,’ speculating whether trouble in Ireland prompted his return, or whether he took the opportunity to kill a now-rival in the shape of Ásl, who the Annals tell us was killed by ‘kinsmen’, possibly including Óláfr, that year.²⁴

In any case, the model of plundering and hostage- or slave-taking seen in 866 appears similar to the next major historically-recorded Scandinavian attack on mainland Scotland, with the siege of the Clyde Britons at Alt Clut, today’s Dumbarton Rock.

AD 870-871

As the Annals note for 870:

The siege of Ail Cluaithe by the Norsemen: Amlaíb and Ímar [i.e.Óláfr and Ívarr], two kings of the Norsemen, laid siege to the fortress and at the end of four months they destroyed and plundered it.²⁵

In 871, the Annals add:

Amlaíb and Ímar [i.e., Óláfr and Ívarr] returned to Áth Cliath [i.e., Dublin] from Alba with two hundred ships, bringing away with them in captivity to Ireland a great prey of Angles and Britons and Picts.²⁶

Note again my argument, shared with Downham and Woolf, that the Amlaíb/Óláfr and Ímar/Ívarr involved in Ireland are the same as those active in Britain, meaning that making a distinction between the leading Vikings from Ireland and Britain is not necessary, as many of the characters (and their aims) would have been shared across the Irish Sea.

Death of Óláfr

In any case, Downham notes that, after his time in Dublin, ‘Óláfr soon returned to North Britain. This suggests that his ambition was not merely the acquisition of wealth, but a campaign of conquest, and perhaps a desire to control the Forth-Clyde line […]’.²⁷

Downham adds: ‘Óláfr is not mentioned in Ireland again and he was killed in Pictland by King Causantín son of Cinaed,’ probably in 874.²⁸ There is also a suggestion, from a translation of the so-called Chronicle of the Kings of Alba by Molly Miller and Benjamin Hudson, that Óláfr was killed gathering tribute, which would, as Downham notes, ‘[suggest] that parts of Pictland were subjected to Óláfr and his associates’ before Causantín put an end to it.²⁹

The deaths of Ívarr in 873 and Óláfr in 874 left a vacuum for Viking ambitions in northern Britain; one that was soon filled by Hálfdan (the brother or close associate of Ívarr, Óláfr and Ásl)³⁰ on his departure from Repton with part of the Great Army.

AD 874-76

I read now from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the events that started in 874, continuing into 875 and 876:

‘This year went the army from Repton; and [Hálfdan] advanced with some of the army against the Northumbrians, and fixed his winter-quarters by the river Tyne. The army then subdued that land, and oft invaded the Picts and the Strathclyde [Britons]. Meanwhile the three kings, Guthrum, Oskytel, and Anwind, went from Repton to Cambridge with a vast army, and sat there one year’.³¹

AD 875: The Battle of Dollar

The Annals of Ulster note that, in 875, ‘The Picts encountered the dark foreigners [in battle], and a great slaughter of the Picts resulted’.³² Downham writes that ‘the battle may have been part of a campaign of revenge against Causantín and an attempt by the associates of Ívarr to regain control of the region,’ adding that ‘The date of the event also coincides with Hálfdan’s attacks on Pictland and Strathclyde reported in ‘The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’.³³

The battle was also noted by the ‘Chronicles of the Kings of Alba,’ telling us that the 875 battle took place at Dollar and that it occurred shortly after Óláfr’s death, which was most likely in 874,³⁴ making 875 a likely date and Hálfdan’s campaigns against the Picts the likely context.

Dollar is located roughly 16.6km (10.3 miles) west-north-west from a Stirling that could still, theoretically, have been reached by Roman roads from the south. Indeed, Maldonado notes that it is probable Hálfdan would have ‘crossed the [River] Forth at or near the Fords of Frew close to Stirling, and then headed towards the Perthshire royal centres’ of the Picts.³⁵

Downham notes that ‘Hálfdan was Ívarr’s brother, and it may have been his troops who were responsible for the victory at Dollar’.³⁶ Thereafter, a reading of the sources could suggest that Causantín was killed by the same force, possibly in Atholl to the north of Dollar, the following year, suggesting that Hálfdan stayed to plunder for a year after his victory.³⁷ ³⁸ ³⁹ Downham adds that ‘this record of events allows the suggestion that Causantín was hunted and killed by the family of Ívarr in their attempt to bring his kingdom under their control’.⁴⁰

From 877 onwards and the death of Hálfdan (Albann) at the hands of Scandinavians at the Battle of Strangford Lough,⁴¹ Viking activity in northern Britain might best be considered a separate phenomenon, so we should now look deeper at that preceding decade of 866-876 in terms of how Viking forces might have operated, and what evidence we have for their physical presence and wider economic and social influence.

Viking Armies in the North

How, then, might Viking armies in northern Britain under Ívarr, Óláfr and Ásl and then under Hálfdan have operated, particularly if, as is implied by ‘some of the army’, the numbers under Hálfdan were a fraction of those at the Repton/Foremark overwintering of 873/4?⁴²

Here, it is useful to think back to the Chronicle’s 865 entry for the appearance of the Great Army. In a typically sparse note, the chronicler still found room to make us aware that the Army had prioritised acquiring horses. This is important, and something we can perhaps neglect: while ships were integral and the probable long-distance mode of transport and baggage train of a Great Army that ensured navigable rivers were a key element of their camps, much of the day-to-day movement was liable to be on horseback, likely using the relic Roman road system to move as efficiently as possible.

Transport Geography: Roman Roads and Great Army Graves

It is these relic Roman roads I turn to now, as I argue that they are central to modelling the routeways of Viking campaigns in Britain. This is despite the plausible suggestion by Kershaw et al. that Hálfdan used ships to reach Northumbria via the Tyne, probably via the Trent from Repton/Foremark to the Ouse and the Humber Estuary en route to the Tyne, and his as yet unidentified camp there, via the North Sea coast.⁴³

Kershaw et al. also think it likely that Hálfdan also reached Dollar and Atholl by ship, but note Strathclyde could have been reached by ‘travelling up the Tyne and connecting with the Roman road (Stanegate) at Corbridge, leading westwards to Carlisle’.⁴⁴ As for choosing ‘Near Felton’ as a taking-off point for the northern campaigns, the authors add: ‘affording easy access to both the Roman road infrastructure and the Northumbrian ‘coastal highway’ (Ferguson 2011), and with commanding views to the coast and along the Coquet valley, it was an ideal base for army members planning attacks on the north’.⁴⁵

Now, the Roman roads that survived into the 9th century would only have been better than the alternative open countryside; what were likely to only ever have been gravelled surfaces, cambered and slightly raised from the surrounds, would have been poor routeways to modern eyes, but would still have represented optimal paths through the landscape, not least as the Roman roads in the uplands of northern Britain tended to follow natural transport corridors dictated by the topography.

Those corridors can be imagined as, for the west, that of the M74/M6, and West Coast Mainline and, for the east, the A1/A68, both of which have provided evidence for Roman roads that would take travellers from England to central Scotland, and thence beyond to Perthshire, being the land routes an army on horseback and foot intent on attacking Strathclyders and Picts would take.

What evidence do we have, then, of the presence of the Great Army in the regions around the Roman roads in northern England and southern Scotland?

For Cumbria, I am indebted to Adam Parsons for his note that burials with possible connections to the Great Army exist at the Cumwhitton Viking cemetery, which is located on low hills immediately to the east of the Roman road. Similarly, Adam also informs me that Hesket, two miles to the south of Cumwhitton, was also adjacent to the Roman road, as is the case for Ormside, which was on the Roman road that comes from Brough.

Similarly, in Galloway, the probable Viking burial at Carronbridge is described by Shane McLeod as ‘a few metres from a cobbled road up to 3m wide, probably Roman in origin, which led to an important river crossing. Burials in earlier landscape features and near roads are well known elsewhere in Britain’.⁴⁶

As with the siting of winter-camps, therefore, there may well be a preference for burials near Roman roads and river crossings (as at Torksey). This preference might also be seen in Yorkshire, with the Viking burial at Leeming Lane, Bedale, next to the A1 and Bedale Beck, a reference for which I am thankful to Stephen Harrison.

Aldwark and Near Felton

From the potential routeways, we now look at the probable bases for operations. For this, we are privileged to have recent excavation materials and ongoing projects from which to inform today’s sketch.

Given the scope of this paper, I will only point you towards one site, that of Aldwark, a large camp replete with the Great Army signifiers outlined by Hadley and Richards. Aldwark is situated 20 km (12.5 miles) north east of York and 5.7 km (3.6 miles) east of the A1 on the banks of the Ure. As noted before, Kershaw et al. consider the possibility that Aldwark is associated with Hálfdan’s forces in the aftermath of his campaigns against Causantín. For more, read the report ‘A Riverine Site Near York: A Possible Viking Camp?’, edited by Gareth Williams.

In moving on, I note that, at Aldwark, as at Torksey, ‘distinctive bullion [economy] practices⁴⁷ […] indicates [that] ‘the driving force for this economic model was southern Scandinavia’⁴⁸ and, thus, fits with the ‘signature’ of the likely Southern Scandinavian dominated Great Army. Moreover, fitting with the model of crossover between Viking groups operating in Britain and Ireland,⁴⁹ Aldwark’s assemblage ‘suggests previous activity in Ireland’.⁵⁰

Near Felton: Base of Operations?

Likely more relevant to our aims today, however, is the Near Felton site, which is situated in the Coquet Valley in northern Northumberland. You can read more about this site in ‘The Viking Great Army north of the Tyne: A Viking camp in Northumberland?’ by Kershaw, Jarman, Weber and Horton in ‘Viking Camps: Case Studies and Comparisons,’ edited by Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson and Irene García Losquiño.⁵¹

The team behind the identification of the site’s potential links to the Great Army were initially alerted to Near Felton via PAS reports on the growing metal-detected assemblage, which included telltale Viking lead gaming pieces seen at camps like Torksey and Foremark.⁵² These hinted at a Scandinavian presence that could be linked to the aforementioned activities of Hálfdan against the Picts and Strathclyders in 874-6, dating, and I quote, ‘to a period following overwintering at Repton in 873/4 and the division of the army into three separate forces, but prior to the establishment of a camp at Aldwark that might date to 876,’⁵³ ⁵⁴ a site the team think is comparable both in terms of potential area (Aldwark is thought to be circa 31 hectares, and Near Felton potentially as large as 49 hectares) and that, and I quote again, ‘both sites likely relate to the activity of the Viking army in Northumbria following its division’.⁵⁵

The site is located 6 km (3.7 miles) to the east of a Roman road that offered connections to Dere Street and Stanegate and, thus, a route towards central Scotland.⁵⁶ Research is ongoing, but there is also the possibility that the promontory site was surrounded on three sides by a river system linked to Thirston Burn and the Coquet itself, allowing parallels to the riverside access of Aldwark, Torksey, and the Woodstown⁵⁷ and Linn Duachaill longphuirt.⁵⁸

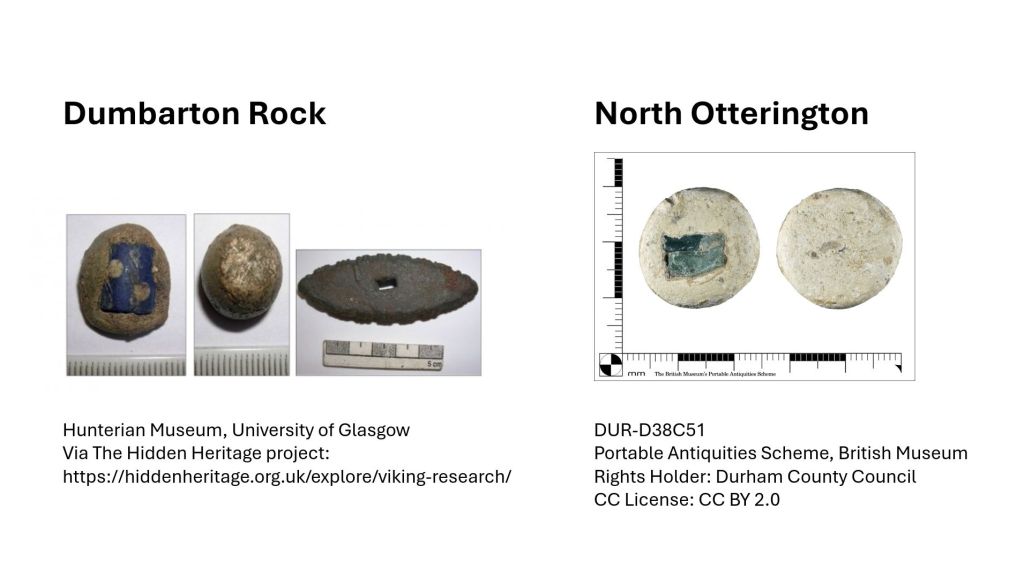

As with Torksey, Near Felton was initially discovered via finds produced by responsible metal detectorists, producing the signature of a potential Great Army site via the presence of stycas, lead inset weights, lead gaming pieces, and also strap ends, giving and I quote, ‘clear parallels with metalwork assemblages at Torksey and Aldwark’.⁵⁹ Notably, the lead inset weights include a glass inset example of a type paralleled in a probable Viking context at Dumbarton Rock.⁶⁰

The Near Felton stycas whose dates can be read match the latest examples from Aldwark, with the authors suggesting that: ‘It thus seems likely that their use at [Near Felton] was contemporaneous with the lead gaming pieces and other items which, we suggest, are associated with the Viking Great Army’.⁶¹

The Archaeological Evidence from Scotland

While no camps have been discovered further north than the potential Near Felton site, there is evidence of activity. Indeed, here we can return to the 870 siege of Dumbarton Rock that, at four months’ duration, speaks to the existence of a siege camp which, we might speculate, could have been similar either to the longphuirt or the winter camps.

Excavations at Dumbarton by Leslie Alcock⁶² ⁶³ produced a small assemblage that speaks to Scandinavian presence at the Rock, with the relevant finds being a sword guard and two lead weights.⁶⁴ ⁶⁵ While the sword provides the headline, it is the weights that are most suggestive of Great Army influence.

One weight is pure lead, with a distinctive barrel shape, paralleled by six at Torksey.⁶⁶ More generally, these ‘oblate spheroid’ weights, most commonly formed of an iron core with a copper-alloy casing, are considered of a ‘standardized’ type of weight used in typically Scandinavian bullion economies, with the oblate spheroid type appearing around 870.

The other weight, of which I was reminded by Adrián Maldonado when writing this paper, is even more telling of potential links to the Great Army: a glass fragment has been pressed into the lead, seen here, providing exact parallels to at least eight of these lead inset type weights that appear to have been a phenomenon of Viking camps in Britain and Ireland. While most lead inset weights have (gilt) copper alloy mounts, the glass inset parallels include Torksey and Woodstown.⁶⁷ ⁶⁸ The other examples are from North Otterington (pictured), Malton, and ‘Near Stamford Bridge’ (all three in North Yorkshire), Archdeacon Newton (Darlington), East Lindsey (Lincolnshire), Melton (Leicestershire) and the aforementioned example from Near Felton (Northumberland).

As the Portable Antiquities Scheme entry for the North Otterington example notes, all (excepting the unlisted Dumbarton example) this particular type of lead inset weight are distributed in the north and east of England, which would fit with a Great Army origin. It is, therefore, critical in any search for Great Army presence or influence in Scotland that we note the type at Dumbarton Rock.

Hoards and Single-Finds

In his book ‘Crucible of Nations,’ Maldonado asks: ‘What lessons might there be in looking at the Great Army from a northern perspective?,’ noting that ‘The sack of Dumbarton in 870 […], and the defeat of the Picts at the Battle of Dollar […] were both led by members of the Great Army.’⁶⁹

The Talnotrie Hoard

In answering questions relating to potential Great Army presence or influence in Scotland, recent research has tended to focus on the Talnotrie hoard, seen here, seemingly deposited in Galloway in the mid 870s. Indeed, as I wrote in my book, ‘A Viking Market Kingdom,’ we should ‘consider the Talnotrie hoard […] with its wintersetl-like combination of [lead inset weights], Northumbrian stycas, English pennies and dirhams, as relating to circa 874-875 Great Army activity in Scotland’,⁷⁰ referencing Hadley and Richards’ work at Torksey and Gareth Williams for Aldwark.

Here, Maldonado adds: ‘recent reassessment of artefacts relating to the Great Army argues that the metal content of the hoard fits well within its archaeological ‘footprint’, including the juxtaposition of Mercian issues with exotic coins of the Carolingian king Louis the Pious, an Abbasid dirham […] and an unidentified fragment of another, along with a decorated lead weight typical of market sites and viking encampments such as Torksey and Cottam’.⁷¹

Returning to the Near Felton site possibly connected to Hálfdan, Kershaw et al. also note that all seven 9th-century strap-ends discovered there to date are Thomas Type A1a examples decorated in the Trewhiddle style, being paralleled with not only the strap-end from Talnotrie, but also most of the strap-end assemblage from Aldwark.⁷²

Beyond Talnotrie: A Great Army Economic Signature?

Of course, and as Maldonado discusses, Talnotrie, single-finds of lead inset weights in Scotland, isolated burials like Carronbridge in Galloway, or the lone dirham from Stevenston Sands in Ayrshire, doth not a Viking army make, nor can we use them to trace the route and stopping points of Óláfr and Ásl, Óláfr and Ívarr, or Hálfdan in the period 866 to 876.

That aside, however, we can see the spread of its influence, if not yet its full ‘footprint’ in these finds, and it will be in their totality where we will see the influence and the extent of this influence of what might be termed ‘Great Army Economics’, with Maldonado arguing for a ‘Great Army trade zone’.⁷³ Indeed, the full title of my book is ‘A Viking Market Kingdom in Ireland and Britain: Trade Networks and the Importation of a Southern Scandinavian Silver Bullion Economy,’ one that emphasises the spread of Scandinavian economic networks in step with that of the monetary and metrological systems that facilitated them and the military campaigns that furthered their reach.

Kiloran Bay

From this perspective, we can look to the metrological influence on another piece of the growing Scottish dataset, namely the Kiloran Bay boat burial and its bullion weight set I referenced earlier in relation to the distinctive metal-weight economy developed in the economic contexts of longphuirt and winter camps.

The Kiloran Bay burial, seen here, thought to date to the period between 870 and 900, contained lead inset weights, balance scales and two (pierced) stycas alongside its weapons and (Irish Sea Region type) shield.⁷⁴ While I agree with Maldonado’s caution on ascribing finds like Kiloran Bay to a ‘Great Army,’ I do find myself asking whether one could be buried in this manner while avoiding looking very much like a follower of Ívarr, being someone involved in the Viking armies and their economic activity across both Ireland and Britain.⁷⁵ ⁷⁶

The Dataset

That aside, the ongoing work by Maldonado on stray finds in Scotland that show potential influence from Great Army activity, such as the lead inset weights, or Scandinavian activity in Ireland, such as silver arm-rings, is vital to the future of research into Viking influence in southern and central Scotland and ascertaining which of that, if any, can be ascribed to the Great Army or merely its economic influence, both positive and negative.⁷⁷

In particular, Maldonado’s dossier into the finds from Coldingham in the Scottish Borders,⁷⁸ which has brought to my attention a lead inset weight (with insular metalwork) and a multi-faceted carnelian bead of the type found at the Repton winter-camp and by my own fair hands in Shetland, seen here, provides us with a glimpse of the future dataset necessary to write the paper he, Jane Kershaw and I will write on what you have heard today.

To this data, we will look to add Courtney Buchanan’s PhD research on stray finds of a Scandinavian nature in southern Scotland and northern England;⁷⁹ ⁸⁰ work that further demonstrates the standing on the shoulders of giants approach we will take to this field of study.

Future Work

Where, then, does all this leave us? I think the caveats by Maldonado caution us on seeing Viking armies everywhere, whether Great Army or not, but do provide the opportunity to launch a twin-pronged research strategy: one that both looks at the economic influence, however removed or direct, of the Great Army, and also one that seeks concrete evidence of Great Army presence, perhaps in the form of a ‘Scottish’ winter camp.

Ultimately, as Maldonado notes, the knock-on effect of the rise of Alba and machinations of Causantín mac Áeda would have major ramifications for the whole of Britain, most notably at the battle of Brunanburh in 937.

To end, it is clear that, with the growing dataset gathered by responsible metal detecting and excavations, allied to increasingly sophisticated remote sensing that allows us to view the potentially very large footprints of Great Army camps beyond what is practicable to excavate, the search for Viking armies in Northern Britain has firm foundations.

Leave a comment